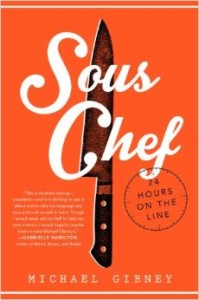

Hello, my name is Michael Gibney, and I have a new book out called “Sous Chef: 24 Hours on the Line.”

It’s about professional cooking: one day in the life of the second-in-command. In the family of a restaurant, if chef were mom or dad and all the cooks were siblings, the sous chef would be the oldest sibling who takes charge of the pack when chef’s not around.

So I’m going to read and excerpt from the book. At this moment we’re in the throes of a Friday night service, it’s gotten extremely busy, food critics have shown up, and one of the cooks has just gone down so the sous chef has to step in and take control of the situation.

(Note: the below excerpt has been edited for time.)

Everything becomes one motion for just this very moment. We switch to auto-pilot.

Finish one fish, move to the next. Start with a hot pan. Start with hot oil. If it’s not hot, wait. Don’t start early, it’ll stick. Check the oven instead, there’s something in there. It needs to be flipped. Out it comes. In goes the butter. Let it bubble. Crush the garlic. Arrosez, flip, arrosez again. Put a pan down. Season the bass, always from a height. The bass goes in, three chars go down. Their skins souffle. Press them to the heat to hear the crackle. The pan’s too hot. The oil smells scorched. Start again. Burner at full tilt.

Now for the mussels. They jump in the oil. Aromas flourish. Here’s a branzino. First of the night. Score its skin. Into the Griswold. Its eyeball pops. Flip it over, into the oven.

On with more gambas, on with more pans, on with more burners. Scrape down the plancha, wipe down the piano, towel your brow. Printers buzz. A new pick, six more fish. Your legs are tired. Tickets blur. Chef needs more. Next up. Cooks moan. Oui, chef! Fat splutters, timers chime, food goes, tickets are stabbed, new ones are plucked up. Organize the boards, start again.

Eight fish now. A pan to each. Eight butters. Eight garlics. Eight flips. Eight arrosez. Eight plates. Eight more picks. Machine gun frequency. Clean pans from Kiko. They’re getting heavy. They drop on the flat top like a bullet blast. Your arms are stiff. The branzino is done. Swing open the oven. The heat blazes. It dries your eyes, blink it out. Grab up the Griswold, bring home the door. The towel is wet, the pan burns your hand. Dizziness, nausea, synesthesia, pain. This is normal. This is what we do. We’re in this together. We’re almost there.

An hour vanishes before you snap back into consciousness and realize that all this time you’ve been operating entirely on instinct. The thought is jarring. You emerge disoriented, knees buckling like a newborn fowl’s. It’s a moment before you can figure out what has brought you back to life. And then it hits you. You just sent out the last piece of fish you had cooking. There’s some tickets on the board but nothing is fired yet. There’s nothing working. You’re finally caught up.

The station is messy. You take this opportunity to do a clean sweep of it. You look around the kitchen. Everybody’s red-faced and sweaty but they too are tidying their stations. They’re folding their towels, changing the spoon water, surveying the mise en place. They slug seltzer from quart containers, belch and stretch. They made it through the push and so have you.

Just then you remember that you have half a cigarette that you clipped earlier on before service started. You extract the soggy packet from your pocket. The cardboard is frayed, the cigarette is bent out of shape. You pluck up the clip with a fishy pair of fingernails. “Off line,” you say, and make your way past Warren toward the loading dock. Chef winks as you pass him. You smile and raise an eyebrow. Out back you kick the door open and light up your smoke.