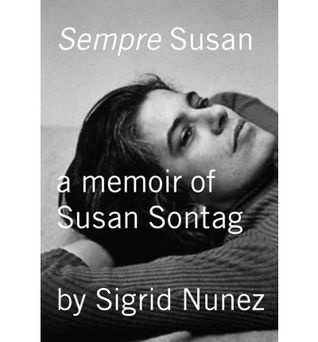

Novelist Sigrid Nunez – then an editorial assistant at The New York Review of Books – helped tend to Susan Sontag’s letters during her first bout with cancer, and they struck up a friendship. Eventually she dated Susan’s son David Rieff, and for a time in the 1970s they shared a household at 340 Riverside Drive. She calls Susan “probably the most important mentor that I ever had.”

This excerpt below picks up when Sigrid decides to get away from the city for a month, and brush up on her writing at a writers’ colony in upstate New York. Susan is not impressed.

Note: The audio excerpt has been edited for broadcast time. Here is the full text:

It was my first time ever going to a writers’ colony, and, for some reason I no longer recall, I had to postpone the date on which I was supposed to arrive. I was concerned that arriving late would be frowned on. But Susan insisted this was not a bad thing. “It’s always good to start off anything by breaking a rule.” For her, arriving late was the rule. “The only time I worry about being late is for a plane or for the opera.” When people complained about always having to wait for her, she was unapologetic. “I figure, if people aren’t smart enough to bring along something to read . . .” (But when certain people wised up and she ended up having to wait for them, she was not pleased.) My own fastidious punctuality could get on her nerves. Out to lunch with her one day, realizing I was going to be late getting back to work, I jumped up from the table, and she scoffed, “Sit down! You don’t have to be there on the dot. Don’t be so servile.” Servile was one of her favorite words.

* * *

Why was I going to a writers’ colony, anyway? Susan wanted to know. She herself would never do that. If she was going to hole up and work for a spell, let it be in a hotel. She’d done that a couple of times and loved it, ordering sandwiches and coffee from room service and working feverishly. But to be secluded in some rural retreat just sounded grim. And what sort of inspiration was to be found in the country? Had I never read Plato? (Socrates to Phaedrus: “I’m a lover of learning, and trees and open country won’t teach me anything.”) I never knew anyone who was more appreciative than Susan was of the beautiful in art and in human physical appearance—“I’m a beauty freak” was something she said all the time—and yet I never knew anyone less moved by the beauties of nature.

To her, it could not have been more obvious: art was superior to nature as the city was superior to the country. Why would anyone want to leave Manhattan—“capital of the twentieth century,” as she loved to say— for a month in the woods? When I said I could easily imagine moving to the country, maybe not right then but when I was older, she was appalled. “That sounds like retiring.” The very word made her ill.

Because it was where her parents lived, she sometimes had to fly to Hawaii. When I said I was dying to visit America’s most beautiful state, she was baffled. “But it’s totally boring.” Curiosity was a supreme virtue in her book, and she herself was endlessly curious— but not about the natural world. Though she often spoke admiringly of the view from her apartment, I never knew her to cross the street to go into Riverside Park. Once, when we were walking together on a campus outside the city, a chipmunk zipped across our path and dove into a hole at the base of an oak tree. “Oh, look at that,” she said. “Just like Walt Disney.” Another time, I showed her a story I was working on in which a dragonfly appeared. “What’s that? Something you made up?” When I started to describe what a dragonfly was, she cut me off. “Never mind.” It wasn’t important; it was boring. Boring, like servile, was one of her favorite words.

Another was exemplary. Also, serious. “You can tell how serious people are by looking at their books.” She meant not only what books they had on their shelves, but how the books were arranged. At that time she had about six thousand books, perhaps a third of the number she would eventually own. Because of her, I arranged my own books by subject and in chronological rather than alphabetical order. I wanted to be serious. “It is harder for a woman,” she acknowledged. Meaning: to be serious, to take herself seriously, to get others to take her seriously. She had put her foot down while still a child. Let gender get in her way? Not on your life! But most women were too timid. Most women were afraid to assert themselves, afraid of looking too smart, too ambitious, too confident. They were afraid of being unladylike. They did not want to be seen as hard or cold or self-centered or arrogant. They were afraid of looking masculine. Rule number one was to get over all that.

Here is one of my favorite Susan Sontag stories.

It was sometime in the sixties, after she’d become a Farrar, Straus and Giroux author, and she was invited to a dinner party at the Strauses’ Upper East Side town house. Back then, it was the custom chez Straus for the guests to separate after dinner, the men repairing to one room, the women to another. For a moment Susan was puzzled. Then it hit her. Without a word to the hostess, she stalked off to join the men. Dorothea Straus told the story gleefully years later: “And that was that! Susan broke the tradition, and we never split up after dinner again.” She was certainly not afraid of looking masculine. And she was impatient with other women for not being more like her. For not being able to leave the women’s room and go join the men.