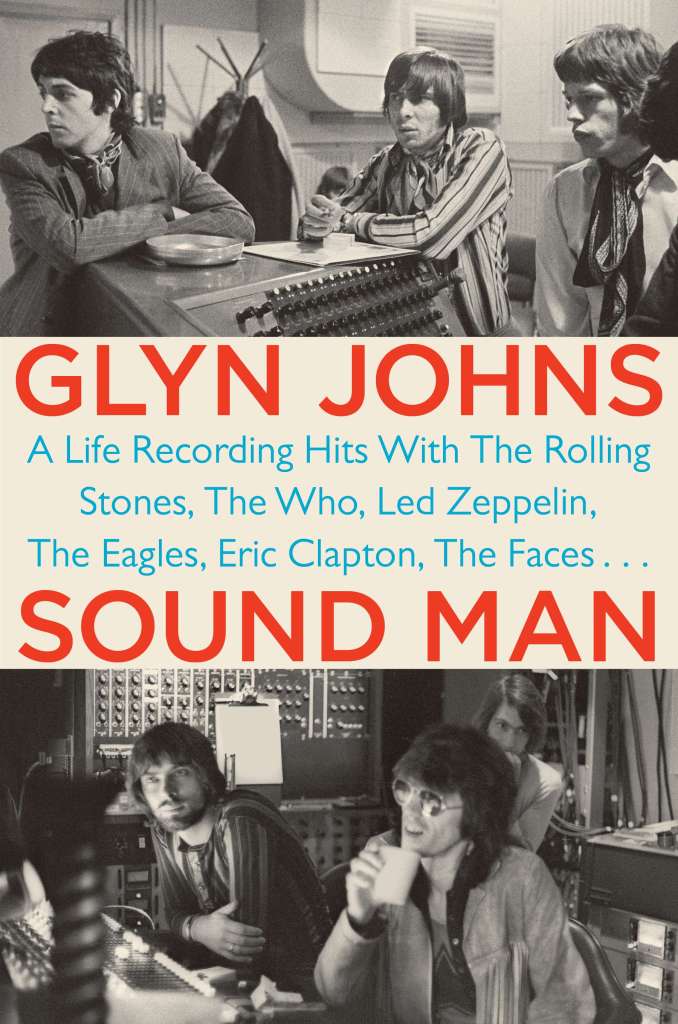

If you tune in almost any FM radio station today, you’ll hear the work of Glyn Johns. He was the engineer — and sometimes producer — of some of the most popular rock songs ever, including classics from The Rolling Stones, The Eagles, Led Zeppelin, and Neil Young. He’s just released a new book about his experiences, called “Sound Man.” He tells Brendan it was all in a day’s work.

Brendan Francis Newnam: Glyn, just to kind of give people a sense of what this book is like and what your life was like, I want to talk about one anecdote that happens in the middle of the book:

You’d just recorded an album with Steve Miller in L.A., and you were in San Francisco, staying with Jann Wenner, the editor of Rolling Stone, and you went to Georgia to see the Allman Brothers. And then you flew on to New York, where you guys ran into Bob Dylan at the airport.

Glyn Johns: Yeah it was a chance meeting. We got off the plane and went to the baggage hall to collect our bags, Jann Wenner and I. He saw Dylan standing in the baggage hall and went over and started talking to him. Since I’d never met him and didn’t know him, I let them get on with it and got my bags and stood outside.

Jann brought him out to meet me, outside on the sidewalk. We had a very pleasant chat. He was complementary about my work with the Stones and so on, and I, in turn, of course, was very complementary about what he contributed to music in general in the previous ten years!

Anyway, he said, “I’ve had this idea for some time now, and perhaps you can help me pull it off” — he wanted to make an album with the Stones and The Beatles.

Brendan Francis Newnam: The Super-est of Super Bands.

Glyn Johns: Well, yes. I mean it would have been a bit odd, really. But anyway, it never happened. but he asked if I could help him facilitate that. So when I got back to England, I called everybody in The Beatles, and I called everybody in The Stones, and put the idea to them.

Brendan Francis Newnam: And Paul and Mick ultimately objected, right?

Glyn Johns: Paul and Mick were not in the least bit interested, and I’m sure they were quite right. They were very sensible about it, I’m sure.

Brendan Francis Newnam: Well, what’s incredible about that story is, first of all, the pace of your life during that time. And then, of course, you have the phone numbers of The Beatles and The Rolling Stones! You were at the center of everything. Now, a little of that is right place, right time to be sure — but what are the qualities that allowed you to be there? Why did all these people want to work with you and how did you get the opportunity to work with them?

Glyn Johns: Well, you have to ask them to get an honest answer to that. It’s terribly difficult for me to know!

Brendan Francis Newnam: If you can arrange that, I’ll do that!

Glyn Johns: Yes! But… one project leads to another. I was fortunate enough to work with some really innovative artists, who, through good fortune, I sort of became attached to, as a result of far more their skills than mine.

Brendan Francis Newnam: Well, I have some theories — maybe I can introduce them to you. Because I anticipated this kind of classic British modesty. So, I think it comes down to a couple things, and correct me if I’m wrong. Reading your book I learned these things. First of all, you never did drugs, is that true?

Glyn Johns: That is absolutely true.

Brendan Francis Newnam: So I’m guessing that you were sometimes, or often, the clearest thinker in the room.

Glyn Johns: Yes, but I think oftentimes, the other people were so out of it, they wouldn’t have even noticed!!

Brendan Francis Newnam: Alright, fair enough. But your skills as a sound engineer were obviously noticed. You made many lasting contributions. For example, with The Who, when they were recording “Don’t Get Fooled Again”, it was your idea to mesh Pete Townsend’s demos of the synths into the recording. Is that right?

Glyn Johns: We did steal the synthesizer part, and played that to the band to play to. I think it was quite a complicated thing for him to put down initially, it took him quite a long time. There was no need for him to redo it all — it would have taken far too long. So we took what he’d already done for the demo and we just edited it to make it a little more concise.

Brendan Francis Newnam: You also created a unique way of recording drums that is now known as the “Glyn Johns Method”. There are a lot of videos of it on YouTube. How to set it up. And you discovered this when recording Led Zeppelin’s first album right?

Glyn Johns: Yeah. What happened on the first Led Zeppelin album, was I discovered, by pure error of my own, stereo drums.

Brendan Francis Newnam: And it happened because you had taken the mic off to record something else and you forgot to switch the channel?

Glyn Johns: Exactly. We cut a track, and we decided we’d over-dub an acoustic on it, I think. The microphone that I was using on the top of the drums, I took that way and put it up for Jimmy Page to play acoustic guitar into. We did that in twenty minutes or however long it took. And I’d assigned that microphone to the left side of the stereo.

And then I put the microphone back on the drums to start the next track. And when I lifted the faders up when I got back in the control room, John Bonham was playing, and half the drums were coming out of the left and half were coming out the middle. And I thought, “well that sounds interesting. What would happen if I put the one that was in the middle on the right?” And there we are; we got this monster drum sound.

Brendan Francis Newnam: So some of the best parts of the book are the moments in between recording sessions. In a way, you were also kind of a sounding board — forgive the pun — for some of these great musicians. I want to play a clip of something you recorded for George Harrison while you were working with The Beatles on “Let It Be.” At the end of the session, he asked if he could play you a song, and you recorded it. Here it is:

Brendan Francis Newnam: I think that’s the actual demo that you recorded in 1969.

Glyn Johns: Well! Where did you get that?!

Brendan Francis Newnam: I found it online.

Glyn Johns: Good lord!

Brendan Francis Newnam: It’s gorgeous.

Glyn Johns: I didn’t know that existed. Well it obviously existed somewhere, but… yes.

Brendan Francis Newnam: It’s absolutely gorgeous.

Glyn Johns: Amazing. Great song.

Brendan Francis Newnam: Do you remember when he presented that to you?

Glyn Johns: I remember it very clearly. I suppose he wasn’t feeling as confident as he might, about presenting material to the others. And, so, he asked if I’d stay behind when everybody’d left, in order for me to record that for him. And I just sat there with my jaw on the floor. I though it was an amazing song.

And he came in and asked me what I thought of it. I thought it was pretty extraordinary. And I said, “Enh, it’s a load of rubbish. You don’t want to do anything with that!”

Brendan Francis Newnam: If you’d said that, you could have changed the course of history!

Glyn Johns: Good lord alive! The mind boggles. No, obviously I told him it was amazing and he should definitely not feel concerned in any way about playing it for the others. Great song.

Brendan Francis Newnam: It really is exquisite. And it’s fascinating to think that you were there to shape it and so many of these other great rock songs.

Glyn Johns: Well, you know what, it’s all very… You’re making it sound very glamorous. I was the recording engineer on the session and it was part of my job. I did him a service.