Brendan Francis Newnam: Alright, ladies and gentlemen it’s dark out and hopefully fog-less here at the Henry Miller Library which means we’re seeing stars.

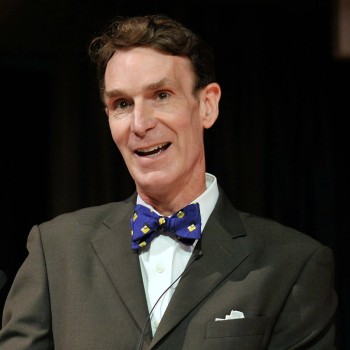

Rico Gagliano: Gazing into the deep black yonder and we figured there would be few folks on Earth with whom it would be better to stargaze with than Bill Nye.

Brendan Francis Newnam: Yes, he’s of course best known for his beloved TV kid’s show “Bill Nye The Science Guy” which ran for five seasons on PBS. He’s executive director of the Planetary Society which advocates for space exploration. He also studied with none other than Carl Sagan and made it through three rounds of Dancing with the Stars. Bill, thanks for joining us.

Bill Nye: It’s so good to be here.

Rico Gagliano: It is great to have you, so here we are lying under the stars.

Bill Nye: It’s lovely.

Brendan Francis Newnam: Wait a second, we need to queue the crickets.

Rico Gagliano: Nice. There we go. Here we are under the stars, now.

Brendan Francis Newnam: Do you guys want? I brought some wine, I figured we could relax?

Bill Nye: Well I mean, I guess, it’s an evening radio show, sure.

Brendan Francis Newnam: Rosé okay with you Bill?

Bill Nye: Yeah, it’s great. So it’s kind of a hotel room cork screw?

Rico Gagliano: Let’s not let it breathe, just pour that right away.

Brendan Francis Newnam: Alright, I’m going to pour it out.

Rico Gagliano: This pairs well with redwoods.

Bill Nye: You know the redwoods wouldn’t be here without the ocean. That’s a strange thing.

Brendan Francis Newnam: How do you mean Bill?

Bill Nye: Well they depend on water in the fog. The little needle leaves are kept moist by the fog, liquid permeates the stomata, apparently. If I’m wrong about that, to the botanists I apologize, but this I can tell you as an observer, they are remarkable. For those listeners who have never seen redwoods, they are amazing, they’re just amazing.

Rico Gagliano: We’re sorry that this is not a visual medium so you can see the redwoods.

Bill Nye: Well for me radio is the most visual medium.

Rico Gagliano: Oh man you’re blowing my mind over here.

Brendan Francis Newnam: Well that’s great because we’re going to have to explain these stars that we’re looking at right now and you know, before.

Rico Gagliano: There’s a lot of them.

Brendan Francis Newnam: You know, you’re Bill Nye The Science Guy, but when did your interest in space come along?

Bill Nye: I do remember very well looking through my father’s telescope which actually had belonged to his scout master and I remember the smell of the cardboard tube, I think it was made from the tube you used to cast concrete footings, cylindrical concrete footings and the moon, it looks like a perfectly round object with a perfect circle but it’s actually deeply cratered.

Rico Gagliano: That’s what you noticed when you looked through the telescope.

Bill Nye: I remember that very, very well, yeah. And then we looked at Jupiter and you can see the moons, the Galilean moons, four big moons of Jupiter and it doesn’t take long to see a move, like for example, Europa’s period is only 85 hours going around this enormous planet.

Rico Gagliano: So you could actually watch the moon move if you waited around long enough.

Bill Nye: Well you can. I recommend it to everyone who’s never done it. Look at Jupiter through a telescope, make a little chart of where you perceive the four pin prick moons are and if you only see three it’s cause one of them is either on the far side or the near side of Jupiter and you can’t resolve it.

Rico Gagliano: That was fast paced entertainment back in the days of Galileo.

Bill Nye: Well, I mean we’re out here trying to be mellow like in the redwoods. I really encourage you because then come back a couple hours later you’ll see the moons have moved.

Rico Gagliano: So that’s what you can see through a telescope. Remind us what we are looking at now with the naked eye.

Bill Nye: There’s like a lot of stars. Like dude, there’s a lot of stars.

Rico Gagliano: Have another sip of rose there.

Brendan Francis Newnam: And they are mostly suns, right?

Bill Nye: Yeah, yeah, sure. It is an amazing thing that our sun is a completely unremarkable star. So does that mean we are unremarkable life forms?

Brendan Francis Newnam: That’s what I’m saying. So we’re not the most important planet?

Bill Nye: Very important to me. When you talk to school kids it’s very common you’ll say what’s your favorite planet? Saturn! Pluto! No, Earth, man. I’m all about Earth, that’s where I grew up, all my friends are here.

Brendan Francis Newnam: And Pluto’s not even a planet anymore.

Bill Nye: And that’s so, okay, here’s my problem, there’s a mission as we call it, a spacecraft which is on its way to Pluto and I went to Cape Canaveral in 2006 for the launch of New Horizons. A relatively low mass spacecraft on top of a relatively huge rocket. The astronauts who went to the moon took a couple days, two and a half days to get there. This rocket went past the moon in nine hours and going that fast it arrives in the vicinity of Pluto next year, Bastille Day, Summer of 2015. So the guy who’s the principal investigator on that, Alan Stern, to him, whatever reason, it’s very important that Pluto be considered a planet. Whereas for me, I’m fine with it not being a planet. Instead it’s this new, cool thing which I like to call the Plutoids. As far as I understand, Dr. Stern doesn’t like that expression for whatever reason. The way I deal with this now is I say we have eight traditional planets. There are eight traditional planets.

Rico Gagliano: Right, and then one punk rock planet.

Bill Nye: And then one that’s something different. By the way, people throw around the expression Trans-Neptunian to describe Pluto.

Rico Gagliano: That’s a David Bowie album I think.

Bill Nye: Which would be fine. It would be fine if you were just going to refer to Pluto but they use the expression Trans-Neptunian to refer to many, many of these objects that we can see from here let alone what you could see from out there at Pluto. This is all cool you guys, it’s an exercise, it’s fun.

Rico Gagliano: Hey, I’m digging it. I like thinking about Pluto with a mohawk. But let’s talk about what we’re looking at right now. You know, everybody knows the big dipper. Give us a deep cut constellation.

Brendan Francis Newnam: Yeah, what’s like the secret?

Bill Nye: Well, you’re never supposed to say your favorite, but I remember sitting there with my dad one night. My father was in prisoner of war camp for four years in World War II. If you guys get a chance to do that I would avoid that. It sounds like a real drag. But there was no light. Only once awhile did they have electricity by all accounts and so he became quite the amateur astronomer, my father did. Anyway, there’s one called Draco.

Rico Gagliano: Oh the dragon? Is that?

Bill Nye: And it winds, yeah, yeah, and it winds between the Little Dipper, the Big Dipper, Cassiopeia, Orion and Pegasus, it winds around all of those stars and it was just left over, it’s like see, I’ll connect all those! That’s like a snake. No, it’s a dragon! It’s a dragon. Fire breathing.

Rico Gagliano: I even understood that. I remember as a kid looking at a map of the stars and being like that’s just the ones they couldn’t fit into any other constellations.

Bill Nye: That’s right, which is no problem.

Brendan Francis Newnam: I was thinking we could maybe get kids even more excited about space if we changed their names.

Rico Gagliano: The constellations?

Brendan Francis Newnam: Yeah, because those names are, Draco, like that sounds like either a restaurant in Brooklyn or a weird, evil guy in a James Bond movie.

Bill Nye: That drives a Jaguar, yeah.

Brendan Francis Newnam: But if you call it something like Beyonce’s Belt. Like that.

Bill Nye: Carl Sagan, when we were in class, invited us to make up our own constellations.

Brendan Francis Newnam: Oh see, great minds think alike. Did you come up with one?

Bill Nye: It was a horse.

Brendan Francis Newnam: Come on, Bill.

Bill Nye: Well, what should it have been? A slide rule? I’m so old.

Brendan Francis Newnam: What about a bow-tie?

Bill Nye: Well it was before I knew how to tie a bow-tie and I would wear one when called upon, but in those days as a college student seldom wore a tie, very seldom had occasion to wear a bow-tie.

Rico Gagliano: How about something cool like a race car? Formula One?

Bill Nye: Yeah, well, I dropped the race car-ical ball. I’m sorry.

Brendan Francis Newnam: It didn’t seem right. So we’ve heard that you always wanted to be an astronaut.

Bill Nye: Sure, I applied a few times.

Brendan Francis Newnam: What’s destination number one? Where would you want to go up there?

Bill Nye: Mars.

You want to go to Mars. Mars is the most likely place to look for life in the solar system. If we were to discover evidence of life on another world, it would utterly change this one. Everybody would think about his or her place in the cosmos, his or her place in space, as I like to say, differently.

Brendan Francis Newnam: I like that, it rhymes.

Rico Gagliano: Well I don’t want to be a cynical, but would that really happen?

Bill Nye: Well did Copernicus change your life? Or Galileo? You have the ability to navigate around the world and that has changed your life for the better. In the same way, if we were to discover evidence of life on another world we would ask ourselves “Does it have DNA?” That is to say, it is quite reasonable, extraordinary, but not crazy that life started on Mars. Three billion years ago Mars got hit with an impactor, stuff whistled out to space, and it got into what we call a homing orbit where it takes a relatively short amount of time to fall from Mars to the Earth. We find amino acids that survive on meteorites so maybe we are all descendent from a martian.

But then if it’s totally different type of life that we were to find on Mars, either way, do you see how that could easily change medicine. Would change the way you dealt with germs for example. And the other thing I like to remind people, “What are you going to discover there?” We don’t know. That’s why we’re going exploring.

Rico Gagliano: So what’s another place maybe?

Bill Nye: Well Europa. I want to go fly by Europa. I’d love to walk around the Europa.

Brendan Francis Newnam: And that’s a moon of Jupiter?

Bill Nye: That is covered with ice, but below the ice is sea water, salty water. Crazy.

Rico Gagliano: What would you do up there?

Bill Nye: We’d look for life.

Brendan Francis Newnam: It’s interesting that we leave Earth and the first thing we want to do is find other people.

Bill Nye: Two deep questions and if you tell me you haven’t asked these questions I like totally don’t believe you. Where did we come from and are we alone? Are we alone in the universe?

Brendan Francis Newnam: Storks and no.

Bill Nye: Storks and no, but for a lot of kids that’s not enough.

Rico Gagliano: What is the possibility that we’re actually going to encounter an alien?

Bill Nye: Well if you’re talking to me, at The Planetary Society, and we are optimistic, we would say in the next 25 years. We’ll mount a mission to Europa, we’ll fly, now what’s happened, what’s changed. Scientists and engineers looked at this in 2010, sending a mission to Europa. Everybody figured we’d have to have a lander, a spacecraft that would land on Europa. It’s something nobody’s ever tried. Then you’d have to have a drill, a thermo drill to melt it’s way through 20 kilometers of ice.

Rico Gagliano: I saw that on “Star Trek.”

Bill Nye: Yeah, well and you do that on Star Trek but in real life that’s quite an expensive undertaking and in the meantime, the Hubble Space telescope observed plumes of water being shot into space by Europa.

Brendan Francis Newnam: And so we might not have to drill.

Bill Nye: Exactly! So you wouldn’t have to do anything. You wouldn’t have to land, you would just fly 45 orbits or something and you would look for insects smashed on the windshield. You’d look for sea ice smashed against some detector and you would do your best with remote instruments to determine if it was something life-like. And if you could go out there as a human and walk around that would be so cool.

Brendan Francis Newnam: You’d have to ice skate though, right?

Bill Nye: Yeah, well we’d set up for that. The reason you’d want to do that, send people to Mars, or Europa, or the moon, it’s been estimated based on data collected when geologists were running around in the Mojave Desert, that what our very best rover can do in a week a geologist, a human can do in about a minute. So if you had a human there you’d just get things done a lot more quickly. But getting a human there and getting him or her back is a lot of messing around.

Brendan Francis Newnam: But, wait a second, so do you want to go there right now?

Bill Nye: Yeah, but I mean, not by myself, I’d want a spaceship and stuff.

Brendan Francis Newnam: Well Rico and I could join you.

Bill Nye: Oh cool.

Rico Gagliano: Yeah, cause Carl Sagan had his spaceship of the imagination, you know?

Brendan Francis Newnam: We had this audio rocket.

Rico Gagliano: It’s right over here.

Brendan Francis Newnam: So you want to go? You can bring your wine.

Bill Nye: Great!