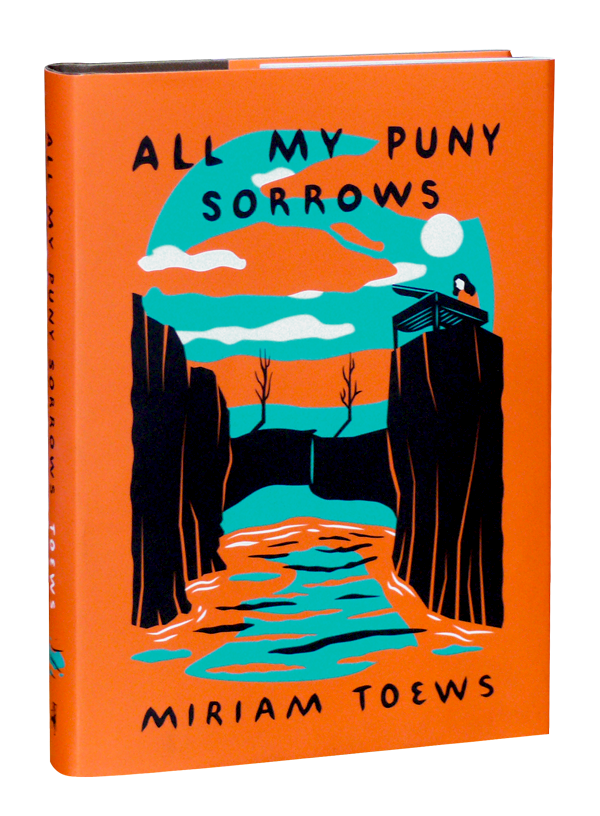

Hi, my name is Miriam Toews. My new book is called “All My Puny Sorrows.”

It’s a book about two sisters, Elfrieda and Yolandi. Elfrieda would very much like to die, and Yolandi, her younger sister, very much wants to keep her alive. And this is a story that comes from my own experience.

Our house was taken away on the back of a truck one afternoon late in the summer of 1979. My parents and my older sister and I stood in the middle of the street and watched it disappear, a low-slung bungalow made of wood and brick and plaster slowly making its way down First Street, past the A&W and the Deluxe Bowling Lanes, and out onto the Number 12 highway, where we eventually lost sight of it.

“I can still see it,” said my sister Elfrieda repeatedly, until finally she couldn’t. “I can still see it. I can still see it. I can still… OK, nope, it’s gone,” she said.

My father had built it himself back when he had a new bride, both of them barely twenty years old, and a dream. My mother told Elfrieda and me that she and my father were so young and so exploding with energy that on hot evenings, just as soon as my father had finished teaching school for the day and my mother had finished the baking and everything else, they’d go running through the sprinkler in their new front yard, whooping and leaping, completely oblivious to the stares and consternation of their older neighbors, who thought it unbecoming of a newly married Mennonite couple to be cavorting, half-dressed, in full view of the entire town.

Years later, Elfrieda would describe the scene as my parents’ La Dolce Vita moment, and the sprinkler as their Trevi Fountain.

“Where’s it going?” I asked my father. We stood in the center of the road. The house was gone. My father made a visor with his hand to block the sun’s glare.

“I don’t know,” he said. He didn’t want to know.

Elfrieda and my mother and I got into our car and waited for my father to join us. He stood looking at emptiness for what seemed like an eternity to me. Finally my mother reached over and honked the horn, only slightly, not enough to startle my father, but to make him turn and look at us. It was such a hot summer and we had a few days to kill before we could move into our new house, which was similar to our old house, but not one that my father had built himself.

And so, my parents decided we should go camping in the Badlands of South Dakota. We spent the whole time, it seemed, setting everything up and then tearing it all down. My sister Elfrieda said it wasn’t really life. It was like being in a mental hospital where everyone walked around with the sole purpose of surviving. It was like being in a refugee camp. It was a halfway house for recovering neurotics, it was this and that. She didn’t like camping.

And our mother said “Well, honey, it’s meant to alter our perception of things.”

“Paris would do that too,” said Elf, “or LSD.”

And our mother said “Come on, the point is we’re all together, let’s cook our weiners.”

The propane stove had an oil leak and exploded into four-foot flames and charred the picnic table, but while that was happening, Elfrieda danced around the fire singing “Seasons in the Sun” by Terry Jacks, a song about a black sheep saying goodbye to everyone because he’s dying, and our father swore for the first recorded time — “What in the Sam Hills?” — and stood close to the fire poised to do something but what? What? And our mother stood there shaking, laughing, unable to speak.

I yelled at my family to move away from the fire, but nobody moved an inch, as if they had been placed in their positions by a movie director and the fire was only fake. Then I grabbed the half-empty Rainbow ice cream pail that was sitting on the picnic table and ran across the field to the communal tap and filled the pail of water and ran back and threw the water onto the flames, which leapt higher then, towards the branches of an overhanging poplar tree.

A branch sparked into fire, but only briefly, because by then the skies had darkened and suddenly rain and hail began their own swift assault, and we were finally safe, at least from fire.