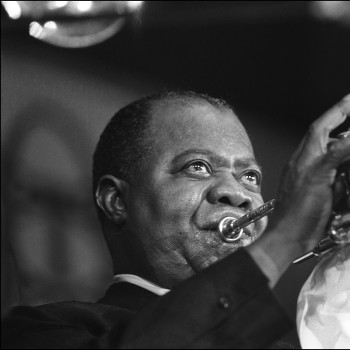

In “Louis Armstrong: Master of Modernism,” music scholar Thomas Brothers investigates the ‘glory years’ of Louis Armstrong’s career – the 1920s and 1930s – during which the jazz musician was simultaneously America’s biggest music star and an avant garde musical revolutionary. His trumpet playing and singing changed American popular music even as he and his band coped with racism, addiction, and poverty.

This is Mr. Brothers’ third book about Armstrong. He tells Rico about Satchmo’s two major stylistic inventions… and the double-meaning of “barbecue.”

Rico Gagliano: And now, time for chattering class, in which we’re schooled by an expert in some party-worthy topic. The topic today is a musician whose work you’ll definitely hear if you attend enough parties: Louis Armstrong. And our teacher is Thomas Brothers. He is a professor of music at Duke University and this week he published his third, very deeply researched book about Armstrong. It’s called “The Master of Modernism,” and Thomas, welcome.

Thomas Brothers: Thanks a lot Rico, it’s great to be here.

Rico Gagliano: So first of all, I think a lot of people think of Louis Armstrong as the voice that always shows up on romantic comedy soundtracks singing “What a Wonderful World.”

Thomas Brothers: Yeah, it’s great — that still is hanging in there, it’s incredible.

Rico Gagliano: It’ll never go away, I think. But he’s considered one of the most important musicians maybe in the history of American popular music. Give us a general reason why, and then we’ll get into details.

Thomas Brothers: Yeah, well he recorded that song, of course, when he was 65 years old. So a lot happened before then! And what I’m working with is what I consider — and I guess what most scholars would consider — really the glory years of his career: 1922 to 1932 is the period covered in the book. When he was

the cutting edge, the avant-garde.

And my argument in the book is that he really creates two modern styles that have tremendous impact on all of jazz, actually. One on the trumpet, and one with his voice.

Rico Gagliano: Why don’t we take that one at a time: Start with the trumpet. What did he do?

Thomas Brothers: Well, this is the period of the Hot Fives and Hot Sevens —

Rico Gagliano: That’s the name of his group.

Thomas Brothers: — Yeah. And he took the ‘hot solo’, which was an established kind of solo in the early 20’s, and he turned it into an art form. The hot solo, as he found it, was something that was there for the sake of variety, basically; it didn’t have to be a great melodic creation. It had to have a lot of rhythmic excitement, it had to have some drive to it, it had to have some bluesy touches. But it didn’t have to be a great melodic statement. He really shaped it into something that you could remember, and something that you could imitate and so forth.

Rico Gagliano: Is there one song that stands out as the defining moment where this style takes shape?

Thomas Brothers: There’s not one, there’s a dozen of them. Let’s take “Struttin’ With Some Barbecue.” That’s a great song, it’s a great tune. We could listen to that. That would be terrific.

Rico Gagliano: That’s great for a dinner-party themed show actually.

Thomas Brothers: Yeah, well, “barbecue” had several meanings actually. One of them was barbecue, an iconic Southern food… but it was also slang for a woman. So there you go.

Rico Gagliano: Awww, yeah. All right; here’s Armstrong’s solo on “Struttin’ With Some Barbecue.”

Rico Gagliano: So that really catchy, hummable solo style comes out. How do people react to it?

Thomas Brothers: They go nuts over it. The Hot Fives and Hot Sevens, they left a recording legacy that you could say is “canonic,” I guess — in that every jazz history text will talk a lot about these recordings — and they became canonic almost immediately. All musicians recognized that this was the way to go. They memorized his solos, they imitated them, and they built on them for their own personal styles.

Rico Gagliano: Let’s move to his vocal style, the second thing that he created. What about his vocal style was so revolutionary?

Thomas Brothers: The vocal style, it’s in 1929, 1930 where this really gets going. He had been singing before this, but this is when he starts to record popular songs of the day. Songs like… “Stardust” is maybe the famous example. Crooners were singing them in a very sentimental way, just wear your emotions on your sleeve. Armstrong takes these popular songs that everybody knows and he just — as Rudy Valli, who was the most popular crooner of the day, said — “He treats a beautiful, romantic song as a madman would treat it.” Other people talk about how he fractures these songs and reassembles them and puts them back together. It is really a radical transformation of what he’s doing with these pieces.

Rico Gagliano: It is amazing how huge a star he became, because he is so idiosyncratic. His voice… it’s like if Tom Waits became a Top 40 star.

Thomas Brothers: It is, it is kind of shocking! In 1932 he was the biggest selling maker of records in the country. Of all genres of music. He himself is very radical in what he’s doing, but it’s so persuasive that people came along with him. You’ll hear that on “Stardust.”

Rico Gagliano: As I said, one of the most revered American musicians ever. Maybe one of the most studied. What did you uncover in your research that still managed to surprise you?

Thomas Brothers: Yeah, you know… I think the biggest surprise, for me, was the early ’30s. I mean, I knew the most popular hits from that period, but I didn’t know all these recordings like I know them now. And the reason it was surprising is because they’d often been presented as a sort of commercial sellout for him.

The Hot Fives, earlier, had been established as the canonic jazz revolution. People talk about that in terms of chamber music —

Rico Gagliano: He’s considered an artist, a real artist, in that period.

Thomas Brothers: — Yeah. And then they construct the ’30s as sort of a popular sell-out, with the popular tune restricting him and so forth. And that’s just not true. Pick up any anthology that covers ’30, ’31, ’32, ’33, and you’re in for a treat. Those songs — you’ll never get tired of them. I mean, we wouldn’t be listening to “Sweethearts On Parade” if it weren’t for his version of “Sweethearts On Parade.” “Stardust” is a different matter — “Stardust” is a legendary song and it’s got a lot going for it — but a lot of these tunes, it’s what he does with them that makes them last today.

Rico Gagliano: All right, well we’ll go out on “Sweethearts On Parade.” And, Thomas Brothers, thanks for schooling us today.

Thomas Brothers: Hey, I appreciate it. Thank you, Rico.