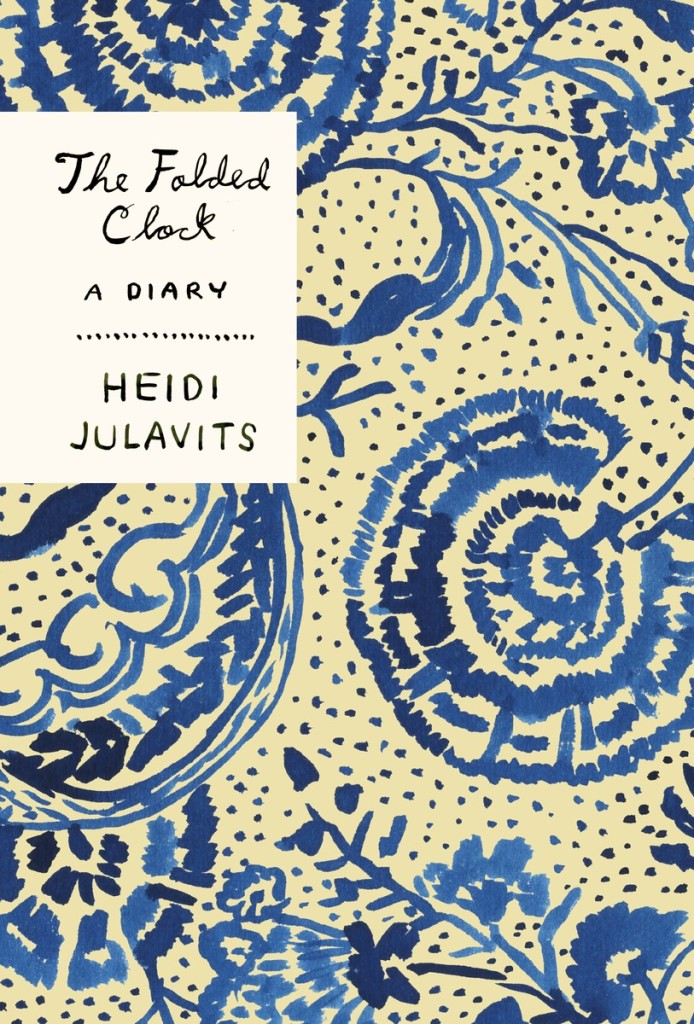

Heidi Julavits has penned four novels, and co-edits the magazine The Believer. She’s also a Mom, a wife and a sometime resident of Maine, all of which she writes about in her new book, “The Folded Clock: A Diary,” which she wrote over the last two years… a little bit at a time.

July 4

Today we marched in our town’s Fourth of July parade. Our float was by far the best–a team of ten (mostly under eight years old) doctors performed a rescue on a sick dolphin, played by a boat builder whom we’d sewn inside a few sheets of sound insulation. The sound insulation had the hand-feel of blubber. It was very realistic to the touch and helped us take our roles seriously.

Unfortunately our dolphin became enamored of the crowd and swam very far ahead of our “ambulance,” and did headstands in the middle of the street, and did not appear in need of rescue. Tired of cartwheeling, the dolphin would finally drop to the ground. We’d blow our whistles, run to him with stethoscopes, roll him onto a pair of canvas firewood carriers, and heft him into the back of the ambulance. Then he’d swim off, ready to do cartwheels again. We were the crowd favorite. We were definitely winning first prize in the float contest.

Unfortunately our dolphin became enamored of the crowd and swam very far ahead of our “ambulance,” and did headstands in the middle of the street, and did not appear in need of rescue. Tired of cartwheeling, the dolphin would finally drop to the ground. We’d blow our whistles, run to him with stethoscopes, roll him onto a pair of canvas firewood carriers, and heft him into the back of the ambulance. Then he’d swim off, ready to do cartwheels again. We were the crowd favorite. We were definitely winning first prize in the float contest.

The judge did not agree. The judge awarded us a second place tie. (Our prize — a $20 bill–was handed to us without pomp at the post-parade BBQ.) Who won first place? We asked the judge. First place, he said, went to the farmers market float.

The farmers market float consisted of three old men driving three old tractors.

“I was impressed that they got those old tractors running,” said the judge.

We shared our second place distinction with the Girl Scout float. The Girl Scouts did nothing but ride in a truck until it was parked and the parade was over, at which point they danced atop the flatbed to “Funky Cold Medina.”

We smelled a rat. Two of the judge’s daughters were on the Girl Scout float! Coincidence? The farmers market takes place on the judge’s front lawn! Coincidence? No and no. We drank beer out of rubber work gloves and bitched about the judge. Oh, the corruption! This judge must be deposed!

I spent the rest of the day polling everyone I saw, including the woman who works in the general store about the float situation. She’s a native Mainer who doesn’t speak much, or at least she doesn’t speak much to me. When I arrive each summer, I’ve decided that the most respectful way to greet her is to fail to greet her at all. But I solicited her opinion on the parade outcome. She seemed to agree that we’d been screwed. “Yeah,” she said. “Who cares about a bunch of tractors?”

I felt vindicated — there is no higher word in our land than that of the woman at the general store — until I remembered: The judge is a controversial figure in our town. Her desire for us to win might more accurately be described as her commitment to never, ever side with the judge.

The judge had arrived from a big city with big ideas about how to fix everything that was wrong here, in his opinion. He was going to install a ferry system to bring tourists from the national park that was eleven miles away by boat (sixty by land). He wanted to build low-income housing on his back property. (Not even the low-income people in town liked this idea.) I believe at one point he talked about starting a university here.

Then he almost burned his barn down by leaving a bag of live stove ashes on the floor. This gave everyone permission to officially discredit him, and then to ease up on him a bit. Now that he’s been proven incompetent, he is tolerated.