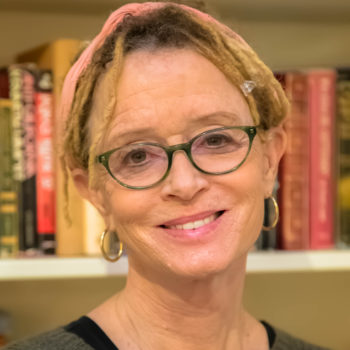

Anne Lamott’s spunky, soul-bearing non-fiction has made her a best-selling author many times over. Her books sometimes investigate spiritual themes and sometimes they’re about very human triumphs and tribulations, like overcoming alcoholism or raising a son as a single mother.

Her latest is called “Hallelujah Anyway: Rediscovering Mercy.” In the book, she defines Mercy as “radical kindness.” When they first spoke, Brendan said he understood the “kindness” part, but he wanted her to explain the “radical” part.

Anne Lamott: Well, probably the most radical part of it all is that it begins with kindness to yourself in the same measure with which you would be very, very kind to others. Sort of automatically — especially women — [we] are outgoingly warm and friendly to other people because we were raised to believe that this was where our value lay. And yet with ourselves, men and women both, we tend to be harsh. And we tend to be easily exasperated with ourselves.

So, the radical part of kindness is about stroking your own shoulder and stopping the bad self-talk. And that’s where my belief in healing — both ourselves and our families and the world — begins, is that we put our own oxygen masks on first.

Brendan Francis Newnam: That’s a good way of putting it, because I would think that some folks would think that the radical part would be embracing a foe, or someone who’s really made you feel bad about yourself, and somehow forgiving them.

Anne Lamott: That’s so hard. I mean, the hardest work we do is forgiveness. But for me, it’s easier to forgive someone I just abhor, than it is to forgive myself some of the time. I am so exasperated, and kind of stunned by how disappointingly I behave. Eventually, I forgive everyone, because there’s that old saying that “not forgiving is like drinking poison and waiting for the rat to die.” And we’re the one who suffers from holding onto resentments and staying clenched up, and bitter.

Brendan Francis Newnam: Yeah. You know, in this book, as you grapple with what it means to be merciful, you weave in stories from different faith traditions and from your own life. One is the biblical story of Jonah, in the Old Testament. And it’s the part after he spends some time living inside a whale. And so, I was wondering, can you fill us in on part two of that story, and tell us what captivated you about it, and how it applies to today?

Anne Lamott: I and my Sunday School kids all love stories about the biggest brats in the Bible. Sort of bitter, goody-two-shoes, and that don’t forgive very well. And so, what happens for Jonah when he lands in Nineveh, is that he’s supposed to go tell everybody to stop being such awful people. He hates them, they’re the enemies of Israel. They’re the Klingons.

And his message to them is that if they start following God, then they’ll be forgiven. But he doesn’t really want them to be, because they’re just such awful people. He thinks they should all die. And that is so me, that’s basically me. But then, what happens is, they hear the word, and they all decide to become people of goodness and mercy. But for Jonah, he’s not having any of it.

So he goes and sits by this tree, on the outskirts of town, just fuming. And in the tree next to him, a worm comes and starts to eat the tree, and Jonah cries out passionately for God to save the tree. And God says, “Really, Jonah? You want me to save the tree and not the people?”

And my kids love it at church because it’s them. It’s us. It’s that we make no sense, we vote against our own instincts, we care about stupidity. And in it all, our generosity towards the common good gets lost. But I love all the stories where somebody is acting really, really badly and doesn’t end up acting all that much better.

Brendan Francis Newnam: Because you can identify with that?

Anne Lamott: Yeah!

Brendan Francis Newnam: You know, reading this book yesterday, I didn’t realize how hungry I was for its message, to some extent. And I did find it was a bomb. You’re very candid about your own failings, and the notion of mercy in general.

I read half of it, and I was walking to the subway. I peeked at my phone and saw the headlines, and it was “North Korea says nuclear attack imminent.” And I’m telling you this, in my mind, I was carrying this notion of mercy, and trying to be more compassionate to myself, and to other people in my life. And I was ready to do that for someone cutting me off in the subway.

But then when it was on such a large scale, I was like, “Oh my gosh.” I was so angry at the leadership of North Korea, at the fumblings of politicians in our country, that I really had a hard time holding onto this idea of mercy in the face of such scary stuff.

Anne Lamott: I know. But that’s why it’s so needed, and that’s why it’s so life-changing. That if you go from being freaked out and contained in your own little ticker-tape, software of your brain, freaking out and thinking who’s to blame, and oh God, what if. It’s that you stop and you start flirting with old people in the subway, and you give people your seats. Or you start to talk to somebody at the health food store who clearly is not doing very well. Just to say, “Oh I love those apples, they’re incredibly sweet. And they are changed. And I am changed.”

Brendan Francis Newnam: So, it sounds like even by kind of triggering an act of mercy, no matter how small, it acts as a salve for something even that might be beyond your control.

Anne Lamott: I think it is like a little bit of medicine to the common pool.

Brendan Francis Newnam: I do want to end with this one question. The title of this book comes from a Candi Staton song, called “Hallelujah Anyway.” I just want to know how that came about, and your relationship to that song.

Anne Lamott: Well, I have a tiny choir at a tiny, failing church in Marin City, California. And the choir is about 8 people, and the congregation is about 40. And every so often, I would hear this song that basically, in a nutshell, says “It’s all hopeless. My feet hurt all the time, I’m getting pink-eye, my kid is scaring me to death. And I’m very, very sad that Justine and Eric are splitting up. But you know what? Hallelujah anyway! We’ll be there for them as they need it. We’re gonna laugh off and on today. We have our music; we have our books.”

Love and grace and mercy are bigger than any bleak crud that the world has to throw at us if we stick together. So, that’s what “Hallelujah Anyway” means.