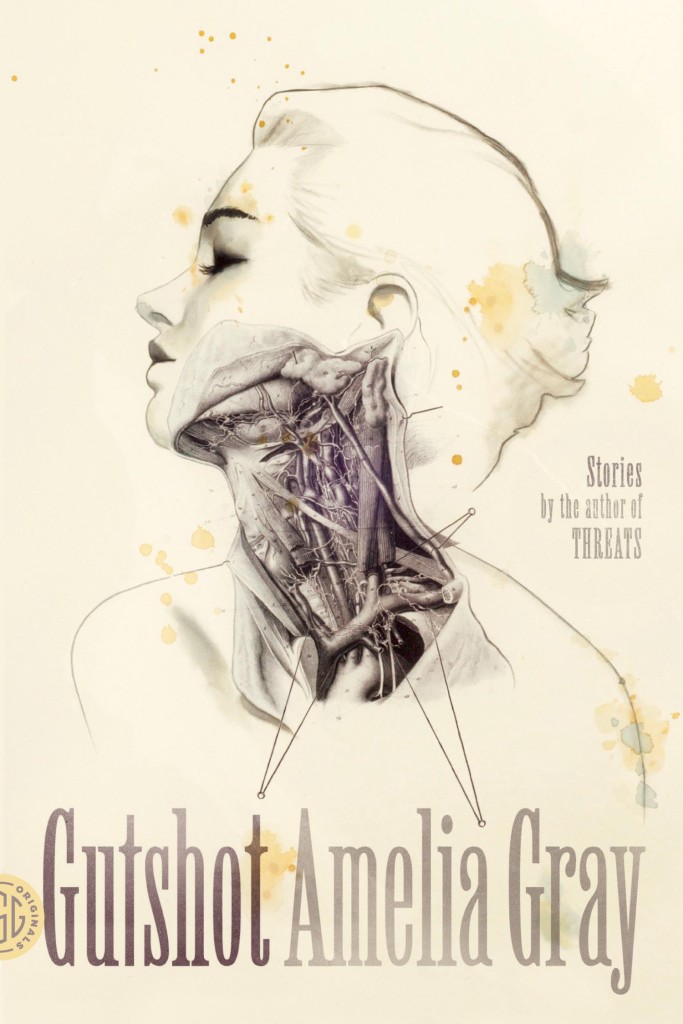

Writer Amelia Gray has earned praise for her darkly funny, unflinching voice, and she’s the featured author at the Pitchfork Music Festival, set to take place from July 17 to 19 in Chicago. Amelia, who appeared on our show in April, returns to read an excerpt from her collection of short stories titled, “GUTSHOT.”

Hi my name is Amelia Gray. A lot of my stories are about the body, they’re very visceral, and this story is called “Blood.” The narrator is a woman looking back on her youth, and in particular, a summer when she was kind of following around her older brother and his boyfriend. So I really wanted to give a sense of summertime; it’s a fun time, it’s an innocent time, but it’s also a really a fleeting time, and even as a young child you get a sense of that.

Your boyfriend’s dad taught us how to kill a mosquito with our minds and our muscle. All you needed to do, your boyfriend’s dad explained, was flex your muscle, and some mechanism would lock the insect there to expand and explode. He was a contractor with a company that worked on houses in the neighborhood. He said all we’ve got is our minds and our muscle and so we ought to know how to use them. He would jab at your arm and say, “Isn’t that right, Joshua?” And you would laugh and rub the back of your neck and agree that he was right.

The neighborhood was the type where all the houses went up at once, so fast that their wood all surely came from the same trees, sheetrock from the same stone. You let me tag along with you and your boyfriend and sometimes he gave me ten dollars to get us some cheeseburgers.

We tried the thing with the mosquitoes for months, skipping the sprays and creams that might ward them off. We were pocked with welts that stung under tanning oil. I remember running across unfinished rooftops, jumping from house to house, but that wasn’t right. It was your boyfriend’s dad who did that and only once, striding a gap onto a garage extension to avoid climbing down and climbing back up. He was strong and cocksure, and seemed fairly confident in his own immortality. I’m still attracted to any man who can whistle.

Your boyfriend was all right. He played the violin. The three of us were lying on a roof once and he said that after death your consciousness snaps out and that’s all. I thought he had been asleep. You said that when you died you wanted your ashes cast into marbles and distributed to your family. I would get the one that looked most like a galaxy, and your boyfriend would get the second. If anyone died, you said, it wouldn’t be one of us. He shrugged and said it didn’t matter either way. We climbed down and looked at the beams where one of the guys had drawn maybe one thousand separate pairs of tits. I was reading a book in school about a girl who folded paper cranes and so this made sense.

The three of us rode our bikes to the community pool and watched the older girls playing tennis. I always found three or four spokey dokes for my bike in the playground by the court, the plastic nibs half buried like they had grown there. We once broke a ramp constructed at the base of a hill for our red wagon and that was the worst thing that happened to any of us, as far as I knew or cared. The idea that everything was fine laid the delicate foundation of my life.

You figured out the mosquito trick right at the end of the summer, before you went to high school and I stayed with the little kids. It was the sweet spot of August and almost my birthday. We were sitting in a half-finished house at the time, drawing in the wood dust on the concrete, when you called my name and I saw it was stuck in your arm, at the prime point of your bicep, placid and feeding, swelling like a tick. Once it burst we shouted with joy. We spread its mess around with our fingers. Afterward I would wonder why the mosquito didn’t push against your skin, why it didn’t strain to free itself, if it maybe knew how special you were.

Excerpted from GUTSHOT by Amelia Gray, published in April 2015 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC. Copyright © 2015 by Amelia Gray. All rights reserved.