Rico Gagliano: Author Jon Ronson has spent decades hanging out with and writing about people on the fringes of society. His book “The Psychopath Test” examined, obviously, the mentally ill. He’s written empathetic, witty essays about religious extremists and about those who believe they are psychic.

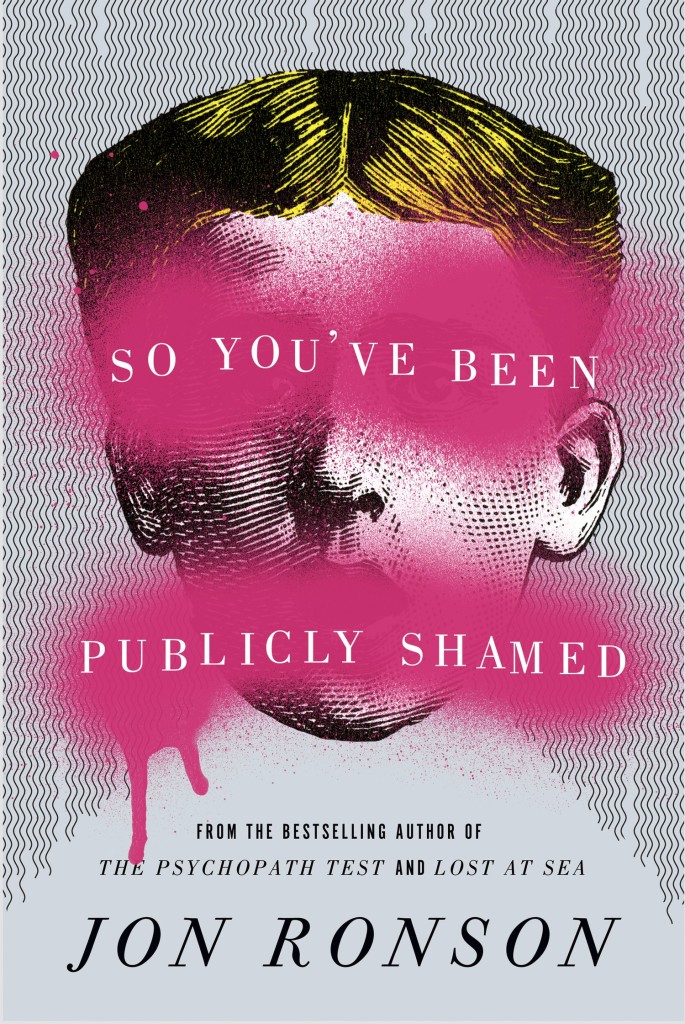

But his latest book is about mostly everyday folks who have been banished to the fringes. It’s called “So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed” and it examines what happens when people like the infamous PR worker Justine Sacco, tweet, for instance, an off-color joke… and find their lives ruined when they’re pilloried in social media. The book comes out this week. and Jon, welcome back to the show.

Jon Ronson: Hi — it’s great to be back.

Rico Gagliano: I think we’ve all seen — or at least heard about — someone saying or doing something questionable, who’s then shamed in the media or online about it. But how pervasive a problem is this, really? Are we really witnessing more of this than we have in the past?

Jon Ronson: Oh, yeah, undoubtedly. I think it’s a renaissance of public shaming — it’s like there’s a war on human nature and its flaws. Obviously, the really huge shamings, the life-destroying ones, only come along once in awhile, and those are the ones I’m concentrating on in my book. But, you know, little mini shamings, little slaps around the face, happen to everybody all the time.

Rico Gagliano: And of course, one of the arguments in the book is that this is one of worst forms of punishment you can endure.

Rico Gagliano: And of course, one of the arguments in the book is that this is one of worst forms of punishment you can endure.

Jon Ronson: You know what, there is nothing worse. And I think anybody who’s gone through any kind of shaming will understand what I’m about to say now: It is profoundly traumatizing to be told you are cast out. If 50,000 people are suddenly tweeting you, and telling you that you’re not a proper human being, and you need to go… that is seriously depressing.

I mean there’s a sort of misconception that, you know, the Internet is not the real world. The Internet is the real world. I met people who went through these kinds of public shamings — and I’m not talking about, you know, politicians who made some terrible transgression, I’m talking about ordinary people who made a joke that landed badly — who didn’t leave home for like a year.

You know, all the great thinkers of the 18th and 19th century were saying “The stocks and the pillory, this stuff is monstrous. We’ve got to stop it.” And yet, we’ve brought it all back on Twitter. And I think the fact that some people will think that, “Oh, it’s no big deal. I’m sure they’re fine already.” There’s a word for that: It’s called cognitive dissonance. We can’t handle the fact that we’ve just ruined somebody’s life, because we like to see ourselves as good people. So, what we either do is say, “Oh, they deserved it because they were a sociopath, or a racist,” or some untrue label; or we say, “Enh, they’re fine, it’s no big deal.”

Rico Gagliano: Well, let me give you an example that’s sort of between, say, a corrupt politician who’s being called out on the Internet, and the people you’re talking about who are having their lives ruined because of an ill-advised joke.

You spend a lot of time talking about the science writer and journalist Jonah Lehrer. Who’s kind of between these two poles. Among other things, for those who don’t know, it was discovered he had made up quotes and attributed them to Bob Dylan, and then he lied about it repeatedly to a reporter. Which for a time, at least, destroyed his career. You seem to believe it’s time to lay off of him. Why does a journalist who lied get a break?

Jon Ronson: The world that I feel comfortable in is a world where somebody’s mistake is within context of wider human behavior, as opposed to somebody’s mistake swallowing them up, and all they become is that mistake. I mean, that’s the world I feel most comfortable in. And there was a moment with Jonah where he tried to apologize, at a lunch that was run by this foundation called the Knight Foundation. And they put a Twitter screen, a giant Twitter screen, behind his head so people could tweet their views on Jonah’s apology live, as it went out…

Rico Gagliano: While he was apologizing.

Jon Ronson: …While he was apologizing. And there was a second monitor screen that was in his eye-line. So, while he was apologizing, people were tweeting, you know, “Jonah Lehrer is just a sociopath.” “This is boring. Jonah Lehrer — boring.” And, “He’s tainted as a writer forever.” It was brutal.

You know, is that the world that we want? Is that the world that we want to create for ourselves?

Rico Gagliano: I’ve brought this up before with you, but especially after reading this book… it feels like it’s your life work in some way to demonstrate a kind of superhuman empathy for people who others deride. And frankly, some of whom have done things that one could argue deserve some derision. Why is that so important to you?

Jon Ronson: Yeah, and I’ve certainly met people, over 30 years, who have done terrible, and believed terrible things; you know, I’ve been outed as a Jew at a jihadi training camp.

But, I don’t know, I just believe increasingly in empathy, and trying to understand somebody. As opposed to sticking your fingers in your ears or being one of those terrible journalists who just, you know, it’s all a big, combative performance. I believe in understanding people.

I mean, once in awhile you meet somebody who is incapable of remorse. I mean, I wrote a book, “The Psychopath Test,” about people who have a sort of neurological absence of remorse. Even with them, you’re thinking, “Well, it’s not their fault they were born that way.”

Rico Gagliano: This suddenly occurs to me: On some level, did you write this because you are afraid that you might one day be shamed over something that was unintentionally offensive to someone?

Jon Ronson: Oh, there’s no question. I mean, I am an anxious person, and the two ways my anxiety manifests itself is: You know, if I can’t get my teenage son on the phone at 2:00 in the morning, my brain really rockets off into hyperspace… And, you know, “Have I done something wrong in my work?”

Actually, at one point in the book I say to Jonah Lehrer, “What happened to you is my worst nightmare.” And Jonah replied, “Yeah, and it was mine, too.”

Rico Gagliano: At one point in the book, you talk about the “Pleasurable rush that overwhelms us,” when we become part of a mob that takes someone down. Do we know from where and why that sensation arises?

Jon Ronson: I think Twitter… a friend of mine, Adam Curtis, the documentary maker, calls it a kind of mutual grooming. That what we do on Twitter is we surround ourselves by like-minded people. So, it’s like it’s a constant approval going on. You know, we say “This person is a monster,” everybody around us congratulates us for saying that, and it’s a great feeling to be told that you’re right. So, there’s no incentive to change your mind. If 100,000 people are tearing apart Justine Sacco for her ill-advised AIDS joke, then there’s absolutely no incentive to say: “I’m not sure that the tearing apart of this woman is justified.” Because everybody else on your timeline is tearing them apart, and it’s much safer and it’s much more comfortable to join in with the throng.

And, of course, what is this the opposite of? It’s the opposite of democracy. Because in a democracy, we want to hear what other people have to say.

Rico Gagliano: Do you tweet differently now?

Jon Ronson: Well… The New York Times extracted my book a couple of weeks ago, and a lot of people emailed me to say, “I’m sending your book to my children, you know, to warn them to be careful before they press ‘send.'”

And my response to that was, you know, “I understand why you would do that, but I kind of think that’s not the message that I want my book to…”

Rico Gagliano: Yeah. That’s self-censorship, in a way.

Jon Ronson: …Yeah, and it’s victim-blaming.

So, yes, I am more careful before writing a tweet, but I don’t like that about myself. And what I would rather is a social media where everybody’s just a bit more forgiving and cognizant of nuances, instead of a social media where everybody’s tiptoeing around some kind of abusive parent.

(Ed. note: See also our interview with Ronson about his essay collection “Lost At Sea,” in which he talks about real-life superheroes, horror-rappers, and where to find strangers’ discarded photographs)