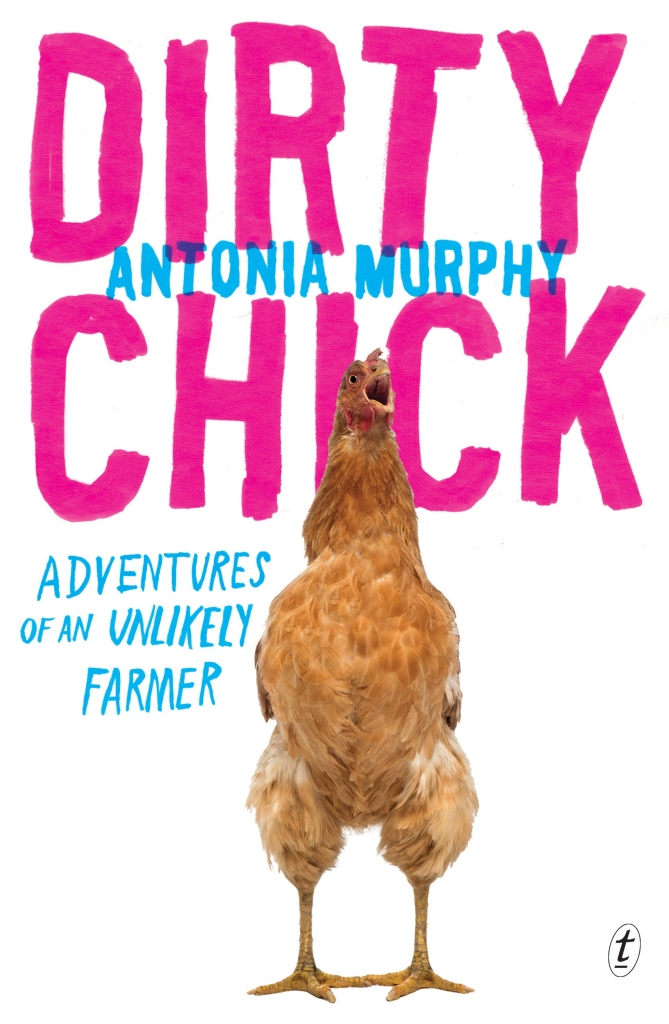

Author Antonia Murphy is an award-winning journalist from San Francisco who, in 2005, set sail with her husband for two years of globe-spanning “boat vagrancy.” They eventually landed in New Zealand, set up a 12-acre farm homestead, and raised a colorful menagerie including chickens, goats, sheep, and alpacas, in addition to their two human children, Silas and Miranda. Her new memoir, “Dirty Chick: Adventures of an Unlikely Farmer,” tells her personal stories of growing farm and family on foreign soil.

Rico Gagliano: Time for chattering class, where we are schooled by an expert on some party-worthy topic. Our topic today: farming. Or, at least, a beginning farmer’s attempts at farming. Our guest is Antonia Murphy. In the early-2000s, she and her husband moved from northern California to New Zealand, had a couple of kids, and found themselves, to their surprise, caring for livestock on a rural farm. Her very funny book about her experiences is called “Dirty Chick: Adventures of an Unlikely Farmer.” She joins us now from New Zealand. Hello, Antonia!

Antonia Murphy: Hi! Thank you for having me.

Rico Gagliano: Thanks for being here, all the way on the other side of the world. As the title suggests, you were probably the last person who would end up on a farm. Before New Zealand, what was your experience with farming?

Antonia Murphy: Uh… Zero. Close to it. I had taken care of my father’s chickens once, except one died.

Rico Gagliano: Yes, this is how the book opens. I don’t know if you can really talk about it on a PG-rated show, but your chicken met an untimely end.

Antonia Murphy: It’s a little painful to talk about. Long story short, don’t keep a bereaved duck in the same enclosure as a chicken. He got a little too amorous and a little too vigorous and the result was tragedy.

Rico Gagliano: Yes, the chicken was ‘loved’ to death. But, yet, you end up taking care of a farm in rural New Zealand. I should point out, you were basically farm-sitting at first, and you were out there in part because there was an affordable school for your child who has a genetic condition. This was not just a lark, but nonetheless, to the realfarmers, you were considered what’s called a ‘lifestyler.’ Tell us the difference between those two groups.

Antonia Murphy: Well, serious farmers don’t talk much. They don’t have much time to talk. They are taking care of hundreds of heads of sheep or cows and it’s their business. Lifestylers are living out in the countryside because it’s beautiful and they might have anything from a few cats and some heirloom tomatoes to we have about 40 animals of different varieties.

Rico Gagliano: Although, 40 animals, to this urban-dweller, that’s pretty serious.

Antonia Murphy: When I say 40, like a quarter of those are our ducks and chickens. You throw in a couple of dogs, a couple of cats, a few alpacas, some sheep and goats, you got yourself a little farm.

Rico Gagliano: Although, small as it is, actually something that really grabbed me about the book is, as soon as you get to the farm, immediately and often, you have to deal with death.

Antonia Murphy: Ah. Yeah. Well, that was really the genesis of the book, that I came out to the country with these really pink-tinted ideas of what farming was like. Basically, being even closer to my food than going to the farmers’ market. The reality was that we had to deal, not just with death, but with dirt, with blood, with worms, with parasites, like all this really gross reality.

I don’t want to give you the impression that I started offing animals left and right. We’re actually really careful with our animals. We take good care of them. But, when we came in, there was a pen full of chickens that the owners, for whom we were house-sitting, [had] on the property, and these chickens had terrible leg mites. They were hobbled. Their legs were bumpy and gruesome and horrific-looking and we had to deal with the fact that they actually had to be euthanized. It wasn’t a situation where they could be cured. So we did it. Actually, by ‘we,’ I mean my husband. Did it as quickly and as painlessly as possible.

Rico Gagliano: And this is just one of many misadventures with various animals. I actually would like to just read you a list of the creatures you encountered and maybe you could just reel off the first thing that comes to mind about each one of them?

Antonia Murphy: Yeah, good.

Rico Gagliano:Let’s start with a rooster.

Antonia Murphy: I will do my best. Roosters are angry and violent. They always become mean.

Rico Gagliano: Alpacas? You mentioned that you still keep alpacas.

Antonia Murphy: Yeah! Alpacas are neurotic and, if you get too close, they’ll spit at you.

Rico Gagliano: At first, when you first get these things, you think they’re going to attack you.

Antonia Murphy: Yeah, they’ve kicked a couple kids. They’re a little high-strung. The big white one has appointed himself the leader of the pack, and, so, if a child gets too close, he’ll kick. But, they don’t have hooves like cows or sheep, they have pads on their feet like dogs, so it’s mostly just a scary experience.

Rico Gagliano: But you do describe just, like, literally being covered with green goo, that you describe as “smelling like a grave.”

Antonia Murphy: Well, I mean, it smells… It’s this sort of fermented slime of the grass that has been digesting for the last few days inside them. So, yes. It’s not cologne.

Rico Gagliano: Delightful. A goat?

Antonia Murphy: Ah! Goat! When they give birth, a giant bubble comes out the backside. A large water balloon came out of my goat. At first I was alarmed, but then I looked closely, and saw that there was a little face in there, and a little hoof. But it was terrifying at first.

Rico Gagliano: Of course! So, you’re saying, you really didn’t know what you were doing. How did you kind of justify yourself to those lifers that had been in it forever?

Antonia Murphy: At first the farmers didn’t take me seriously at all. This might have had to do with the fact that I talk like an American and I wore Halloween animal ears all the time. But they saw that, as we were acquiring animals, they were well taken care of. Because the farmers wouldn’t give me any information, I went and talked to a veterinarian with a whole list of questions. I checked books out of the library. I asked as many questions as I could, even when they answered me in a grumpy tone of voice. And farmers can see – they may not say much – but they’ll look over and they can see if your animals are well taken care of. And so, slowly, grudgingly, now they’re starting to smile at me. Sometimes I’ll even get a wave!

Rico Gagliano: There have been a lot of very earnest books about urban folks moving to the country. This is not one of those. You clearly see the kind of insanity of what you’re doing and the oddness of the community you are a part of, but you’re still there. Was there a moment when you felt like you finally fit in?

Antonia Murphy: When we bought land. That made a difference. Because that meant we were serious about staying there. Also I talk about, in the book, how my son has an on-going medical condition, and he had a bit of a crisis during that year that I tell about. I was away, in America. And our friends drove to the hospital, made sure there was dinner on the table, took care of our younger daughter, they were just right there, no questions asked. That really made me feel like we had come home.

Rico Gagliano: You don’t think the same thing would happen in a different place?

Antonia Murphy: I think people are basically decent anywhere, but, when you live in the city, you can depend on 911. In the countryside, it would take longer for emergency services to get out there than for you to just drive yourself. People have to rely on one another more.

Rico Gagliano: Do you plan on staying forever? Would you ever go back to the city at this point?

Antonia Murphy: I don’t know! Sometimes… I turned to Peter the other day, my husband Peter, and I said, “I miss America.” And he said, “Aww, you’re my Miss America.”