Rico Gagliano: Back in 2003, Andrew Jarecki earned an Oscar nomination for his documentary “Capturing the Friedmans” — about a seemingly idyllic family, two of whom were accused of child molestation.

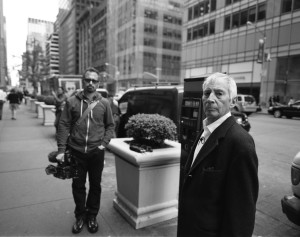

Jarecki’s latest true crime saga is an HBO mini-series called “The Jinx.” In it he examines the case of Robert Durst — one-time heir to a multi-million dollar real estate fortune, whose wife mysteriously went missing in 1982. Some suspect he killed her. Then, years later, a friend of Durst’s was found murdered. And a few years after that, Durst admitted he dismembered another man, but was acquitted after arguing it was self-defense. Durst has long declined interviews, but actually asked Jarecki to interview him for this new show. You can see the results when “The Jinx” premiers this week. And, Andrew, thanks for coming by to talk about it.

Andrew Jarecki: Thanks for having me.

Rico Gagliano: This wasn’t your first time exploring this issue. For those who don’t know, explain why did Durst come to you specifically to be interviewed?

Andrew Jarecki: Well we had — my partner and I — had made a narrative feature about the life of Robert Durst that was called “All Good Things.” And in it, Ryan Gosling plays a character based on Robert Durst. And then, about a week before the movie was coming out in theaters, I got a phone call out of the blue from Bob Durst. So we arranged to have breakfast, and then we showed it to him in Santa Monica in a small screening room. And the idea was he was going to call me a couple of days later, because he would need some time for it to sink in. In fact he called me a couple of minutes after it ended and he said, “I just want you to know I like the movie very much, and why don’t we talk?”

Rico Gagliano: Watching you interview him is kind of a bizarre experience. He’s rather… eccentric, would be the word. At times kind of seems a bit bewildered, or childish, but then also very cagey. What were your first impressions of him?

Andrew Jarecki: Well, I think that as filmmakers, we go thorough a real journey here, because we start with some preconceptions. But when we sat down with him and I really got to know him, I was just constantly surprised. I mean, he’s an enormously smart person. I think it’s kind of an IQ test when you sit down with somebody — you know, when you’re interviewing somebody — how many questions they are “reading you” in advance. In other words, if you ask them, “Hey, when were you born?” if it’s a smart person, they’re already saying, “All right, he’s probably going ask me how old was I when my mom died,” or whatever the next thing is.

Bob actually can read maybe ten or twelve questions in advance. He knows where you’re going, he knows what he’s been accused of, he knows what the pitfalls are.

Rico Gagliano: Do you believe what he says to you?

Andrew Jarecki: Sometimes I do believe him.

I’ll tell you a very quick Bob story:

So we interviewed Bob Durst the first time. And then at a certain point, he decided he didn’t want to be interviewed a second time. So we set up maybe 12 interviews with him, and he cancels every one. We set up the 12th interview, and he calls me a couple of days before and he says, “Andrew, I’m sorry. We’re not going to be able to do that interview. We’re going to have to reschedule.”

And there’s Spanish music playing in the background and he sounds like he’s in a busy restaurant. And I said, “Well why can’t we do it?” He says, “I’m in Madrid. I’m in Madrid and I don’t want to come back to New York because the weather is yucky.” That’s a Bobism.

I hang up the phone, and a few minutes later I’m talking to his assistant. And I say well, “When was the last time you talked to Bob?” He said, “Oh I just talked to him a second ago.” I said, “Oh? What did he say?” He says, “‘When you talk to Jarecki, don’t tell him that I’m in Los Angeles, because I just got finished telling him I was in Madrid.'”

I asked Bob a couple of weeks later, I said, “You know, sometimes you tell me stuff that’s not true, that I don’t think you need to tell me. I’m curious about why you feel like sometimes you tell me things that… that aren’t true.” He thinks for a long time. And he says, “You know Andrew? I’ve been lying all my life. But nobody ever said I was a particularly good liar.”

Rico Gagliano: What do you take from that?

Rico Gagliano: What do you take from that?

Andrew Jarecki: You know, he’s one of those people that will often… he’s so bright that he will answer a question with a story. But I do think that one of the unique things about Bob is that he is incredibly forthcoming about his own oddities, about his own transgressions. About the fact that he doesn’t always tell the truth. There’s something very, very engaging about a person who admits to lying.

Rico Gagliano: Well let’s hear a clip from the film. This is Robert Durst talking about meeting his now missing wife. [ed. note — the clip we used appears at the end of this video clip:]

Rico Gagliano: There’s a technique that you use in this film, and in a lot of your films. In this movie, you’ll see a picture of Robert Durst and his wife, and they’re happy and smiling… but there’s somebody in voice-over talking about how their marriage is falling apart.

And in “Capturing the Friedmans” you’ll show video of a family that looks very happy… and there’s a voice-over of someone talking about how the father is pedophile.

What is it that fascinates you about that idea of the public life, versus what’s actually happening in the private life?

Andrew Jarecki: Well, you know, in our edit room — and whenever we sit around and talk about these things — I always say the same thing. I always say, “Both things can be true.” You can love your wife and also have violence in your relationship. We see it happen every day in relationships.

And I think for me, I’m always interested in monster stories. Because

I always find it so fascinating when people say, “Well, so-and-so is a terrible person. That person is evil.” We say that about other people because we don’t want to imagine that we are capable of anything like what these people are capable of.But if we assume that we’re nothing like them — that we’re a whole different species — what do we learn from spending time with them? Maybe we watch people like a train wreck, or we watch people like a car accident. But the truth is we get a lot more out of saying, “What do I have in common with this person?”

Rico Gagliano: Actually, you may have just answered my next question, but I’m going to throw it out to you anyway: It seems like, at this moment, especially with the success of podcasts like “Serial,” that there is a huge amount of interest in true crime stories. Why do you think that is?

Andrew Jarecki: Well, you know, it’s obvious, with things like “Serial,” that people are drawn to the complexity of those stories. And I certainly was, and I liked “Serial” a lot. And I think, you know, maybe it’s that because we’re living in a world of such wildly superficial media, where things are coming across… and, you know, as much as you can get out of a tweet, or out a text message or out of something in a [blog] posting… that there really is a desire to see the nuances of it.

Because why are we watching these stories, right? We’re narcissistic, we want to see ourselves. Why is everybody watching true crime? To learn about other peoples’ evil secrets. Because they’ve all thought about killing their wife! Because they’ve all thought about doing something terrible! They’ve all thought about stealing money from you know, their employer, or the bank next to them. Many, many, many of them…

Rico Gagliano: I’ve never done that!

Andrew Jarecki: …They don’t do it, But people fantasize about these things. And so, they get a chance to see inside the mind of somebody who has done something awful. So I think these things like “Serial,” they’re tapping into our desire to see ourselves in a more nuanced way, to imagine ourselves in those stories.

Rico Gagliano: I think you’re right. I also wonder, though, if there’s something to the fact that — in recent history — there are many supposedly absolutely true facts we’ve been told… that turned out to not be as true as they were originally portrayed. And I wonder if our interest in stories like in “Serial” — where the truth seems to be hard to grasp — we are more aware now that that’s true; that there are grey areas.

Andrew Jarecki: You know, we learn about Christopher Columbus and that he discovered America. And then you read Howard Zinn, you know, “People’s History,” and all of a sudden you’re, “Wait a second, Christoper Columbus is here, in his own diaries, crowing about how easy it is to subjugate these Indians. That they’re such lovely people, but he could have them all under the knife within a few minutes.”And you think “Oh, so the father of our country, the guy who discovered it all, was a total barbarian!”

Both things can be true. People can be barbaric and they can be loving parents. People can be a lot of things we don’t necessarily expect.