Rico Gagliano: If you read the New Yorker, you’ve likely seen the work of my guest, Adrian Tomine. His clean-lined illustrations have graced the covers of several issues of that magazine, as well as album covers by bands like The Eels. But he’s also considered one of America’s great graphic novelists.

In his acclaimed comic book, “Optic Nerve,” which he started publishing as a teenager, he tells alternately funny and melancholy stories of everyday people struggling with their small, strange lives.

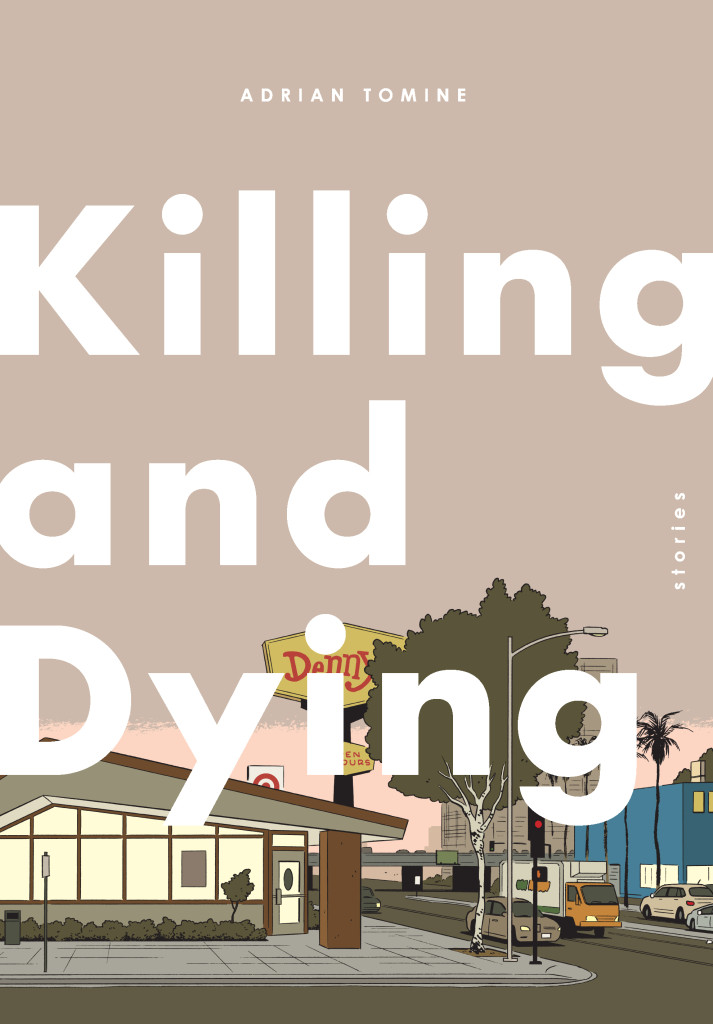

His new collection, “Killing and Dying,” made Publishers Weekly’s list of the most anticipated books of the fall. It consists of six short graphic tales with characters ranging from a stuttering teenage comedian to a Japanese mother reconciling with her estranged husband in America. Adrian is himself Japanese-American and sir, it’s an honor to have you.

Adrian Tomine: Thanks for having me. I appreciate it.

Rico Gagliano: Thanks for being here. You’ve said that you often write a story and then, only later, you realize that it’s semi-autobiographical.

Adrian Tomine: Right.

Rico Gagliano: Which of these six stories ended up being the most personal for you in retrospect?

Adrian Tomine: Oh, in retrospect… I would say any of the ones with schlubby, harried, confused dads are probably the ones that are closest to me [laughs].

I started the book just before we found out that my wife was pregnant with our first kid, and the circumstances of my life just kind of permeated the whole book in weird ways that I didn’t expect, even though it’s a book of fictional stories.

Rico Gagliano: Yeah, I mean, what’s interesting is that when I think of the stories featuring schlubby [laughs] men, they are not about, necessarily, having kids. There’s the one called “Hortisculpture,” and the title story, actually, “Killing and Dying,” kind of features a dad. But both of those are about characters who want to do something artistic, but then kind of learn they actually aren’t very good at it.

Adrian Tomine: Yeah. What does that mean?

Rico Gagliano: Yeah, is that something that was brought up by your wife becoming pregnant?

Adrian Tomine: Well, you know, I suddenly was spending a lot of my time at home with the baby, and my wife was actually pursuing her PhD at the time and writing her dissertation, so the house was just a little chaotic. And I’ve always worked from home, so just even finding the quietness to work on the book a little bit was becoming more and more of a struggle.

And so I thought I was just inventing these completely fictional stories, and they ended up being about dads who didn’t know what they were doing, or cut-rate artists who thought they had some promise and were about to give it all up and just get a respectable job [laughs].

Rico Gagliano: So, was the idea that you were worried about whether you could even be an artist under those circumstances? Or that, you know, suddenly you were wondering whether you were enough of an artist to try to keep making it work?

Adrian Tomine: Oh, well, I’ve always had that “Am I really an artist?” dilemma rattling around in my brain, usually when I’m actually trying to work. But yeah, it kind of brought it into a greater level of clarity when you’re thinking about bills. And it’s hard too because drawing comics was a hobby of mine that somehow, very slowly, morphed into a career. And it suddenly became more clear than ever that it was a real job at that point.

Rico Gagliano: It makes me think about the letters page, actually, of your regular comic book, “Optic Nerve,” where you often include letters from readers who are very critical of you…

Adrian Tomine: Oh, yeah.

Rico Gagliano: …And I used to think that was kind of a brilliant move to show how jerky they were being. You kind of turn the mirror on them. It’s like, “Look at how hypercritical you people are!” But I wonder if maybe it’s because you were actually taking that criticism to heart.

Adrian Tomine: Oh, it’s both of those things, for sure. I’ve also been told by other cartoonists and friends of mine that the letters page is actually their favorite part of the comic, and so it was sort of one of those traditions that kept growing and I could never quite give up.

Rico Gagliano: Why do you think that other artists love it so much?

Adrian Tomine: Probably because, on some level, they agree with all the criticisms and they love seeing someone else say it [laughs].

Rico Gagliano: …Or maybe that they liked seeing that. “Oh, thank God! Other people get these letters as well, not just me.”

Adrian Tomine: Yeah. It could be. But to go back to your question, it has been useful to me to take that criticism to heart.

Rico Gagliano: What is a change that you’ve made based on what other people have said?

Adrian Tomine: I think one of the easy ones to point to is… just the idea of forcing myself to look up from my navel, as they might say. You know, there was a lot of self-reflection, and I had a habit of making characters that kind of looked like me. Once I got the sense that people had had enough of that–

Rico Gagliano: You moved on…

Adrian Tomine: Yeah, it opened me up. Just opening myself up to different kinds of characters and different kinds of stories was really useful to me, I think.

Rico Gagliano: The stories that aren’t autobiographical still seem very grounded in reality, though. And often the twists in them seem so unusual that I wonder if they aren’t drawn from real life — perhaps not yours, but from others. Are they?

Adrian Tomine: I guess it depends on the story in question.

Rico Gagliano: Well, let me– I’ll give you an example. The last story in this collection, “Intruders,” is about a guy who happens to come into possession of the keys to his old apartment from years ago and just starts creepily sneaking into the apartment and hanging out while the new owner is away. Where did that come from?

Adrian Tomine: OK. Well, I’ll tell you a little bit about it, but at the same time, I am a little bit hesitant to decode all the stories.

Rico Gagliano: Sure.

Adrian Tomine: But, in the case of “Intruders,” it really had its roots in this period in my life when I was making a very slow, gradual move from California to New York. And I was sort of going back and forth between the apartments, and I sort of felt like I was living these parallel lives that would almost get placed on hold while I was away, and then I’d come back and the same newspaper that I was reading right before I left last time was still sitting there on the coffee table.

Rico Gagliano: Eerie.

Adrian Tomine: Yeah. I think that was probably the very start of it.

You know, most of these stories, even short ones like “Intruders,” had a long gestation process. So like, the actual drawing of it didn’t take long, but they sort of rattled around in my brain for a long time. And I think that really is where the real work happens for me, is just standing around on the playground, watching my kid, and I’m thinking, “All right. No… that… how am I going to solve that part of the story because it really sucks right now.”

And then, you know, I have to snap out of it and go climb on some monkey bars for a few minutes or something, but–

Rico Gagliano: Although this does bring up my last question which is, you know, if these stories are gestating while you’re watching your kids play on the monkey bars, where does the melancholy of these stories come from? It sounds like that’s a pretty happy situation…

Adrian Tomine: Yeah, it’s a good question.

Rico Gagliano: …You’ve got a pretty happy life.

Adrian Tomine: It is. It’s great and better than ever now, really. I don’t sit down and think, “The tone that I’m going for is melancholy.” In fact, I was really trying to do a lot more humor than before with this book. And then, somehow, my dark cloud of a personality still pervades everything.

I hope the tone of this book will sort of be taken as a strange mix of that melancholy quality with comedy because that really is something that you’re reminded of all the time when you have little kids. I’ve got a six-year-old and an almost, a one-year-old now. So you kind of have these extremes of the human experience on a minute-to-minute basis [laughs].