Each week you send in your questions about how to behave, and here to answer them this time is author George Saunders. He is a bonafide MacArthur genius, and he has won international acclaim for his work in almost every prose form from hilarious satire to short stories to a children’s book.

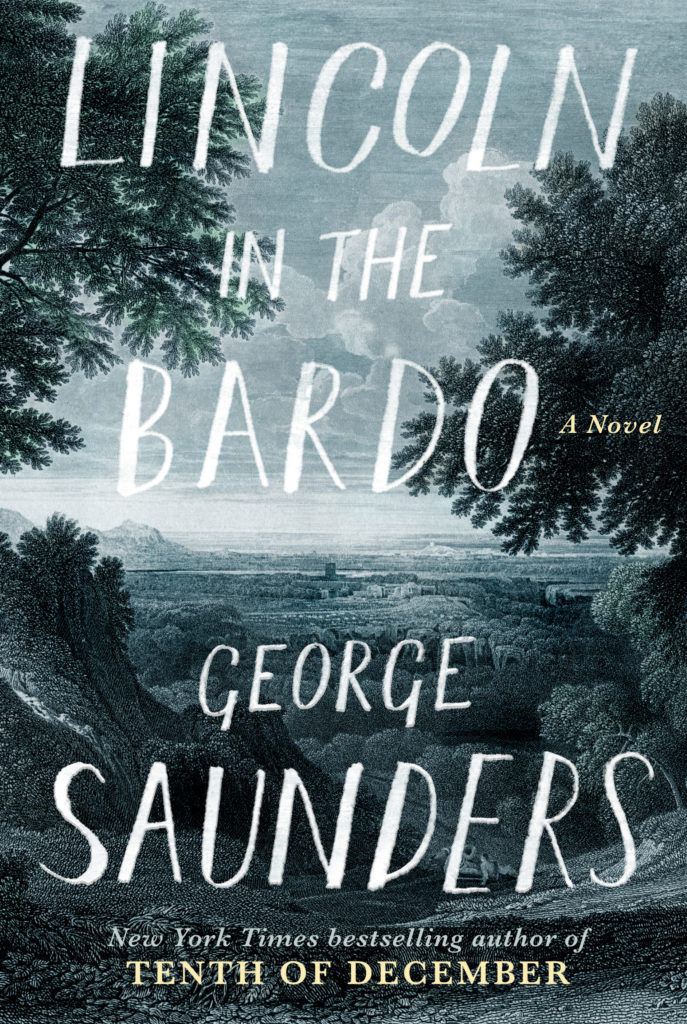

But somehow, his newest work, which is called “Lincoln in the Bardo,” is his first novel. Before answering our listeners’ etiquette problems, he talked with Rico and Brendan about how he discovered the story that became the basis for his debut novel, how his previous non-fiction work factored into his writing process for this book and more.

Interview Highlights:

On why this story became his debut novel

George Saunders: The book just was like, “All right, I need more than 28 pages.” And I try to keep it on a short leash like, “Don’t bloat, don’t bloat up!” And then there was one day where it got to maybe 45, and I’m like, “I think I like it so far, and we’re only an hour into this story.” So, I kind of just reluctantly agreed. Because I was digging the idea of just being only the story writer. I think [there’s] kind of a purity in that.

When I was younger, one of the first things I ever finished was a novel that — it’s now a joke in our house. I’ll give you an idea of its literary qualities. The title was “La Boda de Eduardo,” which I think means, like, “Ed’s Wedding.”

And I spent a year on it when we were young, 700 pages. And I got through it and kind of ceremoniously handed it over to my wife, like, “Honey, I think you’ll see we’re sitting on a goldmine here.” And she made it about three pages in, and I was spying from the next room, and she just was sitting there with her head in her hands. So, that made me a little gun-shy about the whole novel idea.

On what made him interested in the story of Abraham Lincoln’s son, William Wallace “Willie” Lincoln

George Saunders: Years ago, maybe in the ’90s — we were in D.C., driving past Oak Hill Cemetery, and my wife’s cousin mentioned that story, that Lincoln’s son had died, and that Lincoln had been so grief-stricken that, according to newspapers of the time, he’d actually gone into the crypt. And the phrase that got me was “on several occasions.”

So, I had a writing teacher tell me once that it’s very important to distinguish between the stories you should write and the stories you think you should write, and I had that one in the latter category. It sounded like a nice idea, but, at that time especially, as a comic writer, I thought, “I don’t know.”

It seemed too earnest, and I really felt — I think correctly, at that time — that my little tiny bag of talent wasn’t quite big enough to take it on. So then, about 2012, I had a lot of books out and stuff, and my mind would always go to that little anecdote when I was happy, artistically happy or personally happy, just like, “Oh, yeah.”

Rico Gagliano: Why?

Brendan Francis Newnam: It’s so macabre.

George Saunders: Yeah, no, it was the sense of form. I could sort of imagine that the crypt and the… I don’t know, just the mental image that came to mind. I could just feel that there was something really beautiful and sad, but also maybe even funny in it.

And so, about 2012, I had a little talk with myself, like, what is stopping you? And the answer was: well, you’re scared, you’re afraid you don’t have enough talent, the material’s potentially too beautiful. So, those are not good reasons to stay away from it. So, as kind of a midlife gift, I said, “All right, I’m just giving myself three or four months to fart around with this.”

On how he came up with the novel’s purgatory setting and the use of ghost-like voices to drive the storytelling

George Saunders: Well, one of the artistic principles that I internalized way back when was the idea that it has to be fun. When you turn your mind to an idea, it’s got to be exciting to you. And part of that is that whenever you get to a place where the storytelling becomes banal or becomes boring to you, you’ve got to veer off like crazy.

So, when I thought about that Lincoln anecdote, the first thing that came to mind was, “Well, who’s narrating this thing?” Because he’s the only person there. I didn’t want to write a close third person on Lincoln. That just sounds like a novella from the point of view of Jesus. It’s beautiful, but I couldn’t do it.

So, I became aware, pretty soon, that the narrators had to be ghosts because there’s nobody else in there. And then, I found myself really having an aversion to that sense where you go, “A white mass drifted in from the left,” or, “A ghost came in.” I mean, I never say that they’re ghosts. I don’t even know what they are. They’re dead. But it just felt like a speed bump that I didn’t want to have to deal with. So then, the idea of just having the whole story be in monologues came to me.

Brendan Francis Newnam: So, you had to avoid the word “ghost,” but why choose the word “bardo”? Are you a practicing Buddhist?

George Saunders: I’m a beginner practicing Buddhist, yeah. And really, I wanted to avoid the word “purgatory” because I was raised Catholic. And, in that tradition, at least as I understood it, purgatory was kind of like detention, like you screwed up. You have an impure thought, and then you’re in detention for some end of days.

So, it’s bleak, but in what I had come to understand of Eastern traditions, there was a notion that whatever you experienced after death would be closely tied to what your mind was doing right this minute. It’s so touching, that idea that you would kick off, and then you’re still you. And you’re like, “Wait a minute, I can’t die now. My book just came out!” And I know that that would be me. Like, “I didn’t read all the reviews!”

On how his non-fiction work factored into his writing process for the novel

George Saunders: So, I think that, for me, the non-fiction stuff is really important, just as a way of keeping myself honest. My thing is that human beings, one of our safety nets is that we make concepts up about the world. We have a political viewpoint, we have an understanding of how things work, which we have to have to survive. But I think it’s pretty good every now and then to just topple that over. Get yourself to descend into a state of real confusion, like empty-headedness. And, for me, these trips really help.

You think you know what the Trump movement is. You go, you find out you’re wrong. You think you know what the border is. You go, and you find out you’re wrong. And there’s always this beautiful period, it doesn’t last very long because I’m a dummy, but a beautiful period where you really aren’t sure and you’re sitting there with your own uncertainty, genuine, like, “Shoot, I’ve got to write this thing, and I have no idea what’s going on.” All my tidy ideas in which I was the hero are all overturned. So, I think, especially for someone who aspires to write fiction, that’s a really good — almost like a housecleaning to do on yourself. A conceptual housecleaning.

Etiquette

Is it disrespectful to dog-ear a book?

Rico Gagliano: Here’s our first question. It’s from Kay in Brooklyn, very straightforward. “Is it OK to dog-ear a book? A teacher once told me…”

George Saunders: Dog-ear?

Rico Gagliano: Like, to push down the corner of the page.

George Saunders: Oh, I see.

Rico Gagliano: “…A teacher once told me that it was disrespectful to the work. It is very convenient,” says Kay.

George Saunders: Well, I think if you can get the dog to stand still long enough, it’s good. No, actually, I know that feeling, and I think I was told that by a nun at some point. So, when I go to do it, that thought arises. And then I guess I feel like, is it better for me to yield to my inner nun and not do it, or better to do it?

And then, I just ask, well, how would I feel afterwards? So, I guess, in a sense, I’d say in so moral questions, the thing is: there’s the action, and there’s the reaction that you have to it. And if you can deal with the reaction, go ahead and do it.

Rico Gagliano: But I think you’re overthinking this a little bit. If it’s your book, who cares? I don’t understand, like, nun or no.

George Saunders: But if this person has in her head that — as I do — that it’s vaguely disrespectful to the text, then I think you just go, “OK, I have that feeling. What’s going to make me feel the best afterwards?” And what I do is I tend to go get a bookmark, and then I just feel like, all right.

Brendan Francis Newnam: I think I would weigh how I would feel dog-earing the book versus getting out of bed in the cold, walking to find a bookmark to put in the book.

Rico Gagliano: You’re going a long way to satisfy that inner nun, it seems like, George.

Brendan Francis Newnam: Well, Kay, if you can live with yourself, dog-ear away!

Domineering book clubber

Brendan Francis Newnam: Our next question comes from Andrea in Ohio, and Andrea writes: “Someone in my book club dominates the conversation. She has the strangest theories about the books sometimes. How do we wrest control from her and let others talk?”

Rico Gagliano: Uprising.

George Saunders: Well, I guess one thing would be to consider that she might be correct. She might be the only one who’s right. No, actually, this is sometimes a problem in creative writing workshops, which I teach, and the only answer I know to that and a million other writing critique questions is to move this person’s critiques from the general to the specific.

You know, in workshops, someone will say something kind of hurtful, and the only way out of that is to keep asking the person to be more and more specific. So, you know, “Your story sucks. I hate it,” can get talked down into…”

Brendan Francis Newnam: General!

George Saunders: Yeah, can get talked by specifics into, “Page four lags a bit in energy.” And the latter is very easy to hear. So, I bet you, if this person was encouraged by the group to be more specific, she might find herself speaking less.

Rico Gagliano: Oh, I see. Because the problem here is that her theories are weird. If you ask her to get more specific, they may just get crazier and crazier endlessly.

Brendan Francis Newnam: But they may dissolve because she really is trying to lay out the logic of her gut reaction.

Rico Gagliano: Well, give it a try, Andrea. I don’t know. I think you’re doomed.

Catching the dirty dish communal kitchen culprit

Rico Gagliano: Here’s something from Marcus in L.A. Marcus writes: “I will often find dirty dishes abandoned in the communal workplace kitchen, many encrusted with oatmeal remnants. We have an idea who this culprit is. Is it OK to call him out? Also, should we set up a trap to catch him in the act?” Wow, like a mousetrap.

George Saunders: I think you just hold a meeting. Then, you just say, “Hey, somebody’s leaving us some crappy dishes in the thing, so let’s all remember not to do that.” And I bet the person would notice it. Am I being too optimistic?

Brendan Francis Newnam: Is that how it works in your household, if you called a meeting in the household, and you were kind of passive-aggressive? You were like, “Someone keeps leaving a cereal bowl…”

George Saunders: Well, I don’t know if that’s passive-aggressive if they’re really not sure who it is. I think it’s respectful. You call everybody together and say, “Without naming anybody, let’s just remind ourselves of the communal rules of cleanliness.” And actually, after that, if the person does it, I don’t see why you couldn’t go up to him and say, “Craig, we love you. And also, Craig, stop dog-earing my book.”

Brendan Francis Newnam: “We have so many problems with you, Craig.”

Rico Gagliano: I think you have hit on the key, though. You should go up to him personally. You don’t call him out publicly. You don’t send an email out to everyone in your workplace going like, “Guess what?”

George Saunders: I think so, yeah. I think — what is it? I’ll quote Mao Tse-tung: “For a retreating enemy, build a golden bridge.”

Brendan Francis Newnam: Also, Craig, why don’t you eat your oatmeal at home, dude? It takes five seconds to make, and you don’t need to make it at work.

George Saunders: I’m really terrible at giving advice. My feeling is really that most stuff like this, you try anything, and then, from the blowback, you can figure out what the next step is. I’m not big on etiquette advice.

Rico Gagliano: You once parodied advice columns in an essay you wrote called “Ask the Optimist,” in which you, the columnist, eventually blow a fuse and start ranting at your readers. What was the inspiration for that?

George Saunders: I think it was just something about that American, happy-faced feeling. It’s basically denial energy, so everything is wonderful, you know? You drive a spike through my head, and I say, “Oh, thanks for the new coat rack!”

So, that sense that you can never criticize anything or negate anything without being considered kind of a buzzkill. So, that optimist guy was just taking terrible situations and putting this false optimistic sheen on them.

Brendan Francis Newnam: Yeah, so it’s like, “Actually, encrusted oatmeal in a bowl looks beautiful. It looks like it’s a special piece of pottery.”

George Saunders: That’s right. “Thank you for this sculpture.”

Dealing with someone who constantly forgets your name

Rico Gagliano: Well, I’m afraid we have to ask you to provide one more piece of advice. Our last question comes from Julia. She writes in via our website. We don’t know where she’s from. She says: “If a member of your social circle keeps mis-remembering your name when they bump into you at parties, should you keep correcting them or just roll with it and adopt the misremembered name as a kind of temporary pseudonym?”

George Saunders: Oh, that’s a tough one. I think I’d probably correct like, seven times, and on eight, you just sort of let it go. I guess you could also purposely call that person by the wrong name.

Rico Gagliano: Yeah, I like that spirit. There’s a person at our office I call “Linda,” but her real name’s Melissa, but I didn’t know her name for years. And so, she just started — like, when I said “Linda,” she would respond. And now it’s just an inside joke that makes me feel bad and remember I misremembered. It’s actually a good punishment.

Rico Gagliano: Oh, I see.

George Saunders: But it would’ve worked that if she started calling you “Larry,” would it sort of subtly clue you into the fact that you might want to go back and reconsider?

Rico Gagliano: That sounds like there’s a lot of comité there, right? It’s kind of like, “You called me a weird name. Now I’m calling you a weird name. We both are in on the joke now, and now we’re both friends and pals.”

Brendan Francis Newnam: “Oh, I didn’t leave the oatmeal in the sink. That was Larry. That wasn’t me. Ask Linda. She’ll tell you.”

George Saunders: It wasn’t Craig.