Gael García Bernal is one of the most respected actors and producers in the world (just ask Time magazine, which named him one of the year’s most influential people). He first earned raves in films like “Amores Perros” and “The Motorcycle Diaries.” And we talked to him last year about his starring role on the Amazon series “Mozart in the Jungle” — which earned him a Golden Globe.

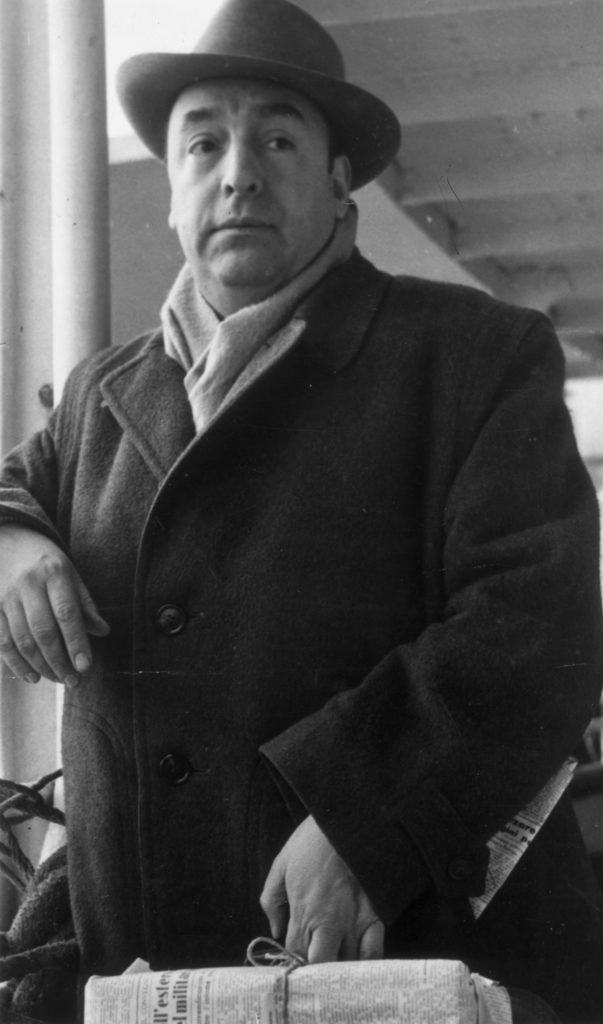

Gael’s new film is the neo-noir, darkly comic period piece “Neruda” — Chile’s entry for the Best Foreign Film Oscar. It details a few years in the life of the Nobel Prize-winning Communist poet and politician Pablo Neruda, who, in the late 1940s, went into hiding after the Communist Party was banned in Chile. Gael plays a jaded cop, maybe a little too convinced of his own genius, who’s tasked with finding the poet.

Gael happily told Rico why “Neruda” intentionally blurs the line between fact and fiction… and why art and politics do mix.

Rico Gagliano: The movie drops you right into the middle of Neruda’s life. It kind of expects us to know a little bit about his importance, and the politics of the time. How much did you know about him before taking on this film?

Gael García Bernal: Well, I mean, growing up in Latin America, when you’re in High School, you enter the world of Neruda for like two months.

Rico Gagliano:Two solid months, seriously?

Gael García Bernal: Yeah. I mean, because his work is so vast! He wrote about everything. He was very prolific, and he was also a politician, a great cook, a great collector…

Rico Gagliano: He was a great cook? That’s not mentioned in the movie.

Gael García Bernal: It’s not mentioned, but it’s implied, because he’s cooking a couple of times.

Rico Gagliano: Yeah, that’s true. At one point he’s dictating poetry while chopping up a chicken or something.

Gael García Bernal: Exactly. A fish.

Rico Gagliano: But even so, we should say, as much as you get all these details about Neruda into the film, this is not a realistic biopic.

Gael García Bernal: I mean, it’s like what Herzog says, you know — if you want reality, well, just look at a phone book! Because that gives you, like, real information.

But really, what survives us is our work. And we approach Neruda through his work, through his Nerudian world that he built. Then you can really, like, get a sense of who this person was.

And basically, what a poet kind of defends is the fact that you can live many lives within one life. So, it’s a film that’s inspired by the work of Neruda… It’s [also] a cinematic thriller… it’s a neo-noir police chase…

Rico Gagliano: Yeah, it’s true! Like, what is it?! It’s a noir. It’s kind of funny. There’re almost slapstick elements in it, at moments. There’s deep drama… which I guess is all kind of summed up in his work.

Which of those parts of Neruda is most attractive to you?

Gael García Bernal: Well, I mean, something that struck me strongly is just… there is something about the fact that you’re willing to show what you wrote to millions and millions of people. To put it out there in the open, it requires a lot of guts.

Rico Gagliano: Particularly when you’re writing extremely political poetry at a time when that can get you, in this case, exiled.

Gael García Bernal: Exactly. I mean, there’s many comparisons that we can do with what’s happening nowadays. He was a communist Senator and he wrote poetry to incorporate the marginalized members of society into society —

Rico Gagliano: Yeah, he was always writing about the working class.

Gael García Bernal: — Exactly. And I mean, most of the victories that we can talk about — social victories nowadays — were made by these people that started to incorporate art into politics in many ways. And that’s something that, well… right now it’s kind of not happening.

Rico Gagliano: Yeah, and I was going to ask you: You yourself have starred in or produced a number of movies about left-wing politics. You played Che Guevara twice. You produced a biopic about Cesar Chavez. You co-directed a series of shorts for Amnesty International about central American migrants.

But, it’s true; it does feel like art — and even media in general — doesn’t seem to have as much impact on politics today as it maybe did in Neruda’s time. So, as a political artist, to an extent, are you just sisyphusian? You’re just pushing this stone up the hill?

Gael García Bernal: No. I mean, that’s another interesting question as well to ponder. No — because I don’t think poetry has lost its power. Maybe it’s relevance in everyday discussion, maybe. But it’s power, no. I mean, it’s like saying that music is no longer… that people don’t react to music. I mean, people react to poetry, people react to music, people react to all these reflection processes we have as humans.

But obviously, saying like, “My film is political and my film is gonna change the world”… you fail. Because you can’t define that. What you can do is something that, eventually, might have that consequence. Eventually, it might accompany a movement or a change that’s going on, or be a catalyst of something that’s happening. But it cannot be, by itself, The Thing That Changes The World.

And to say that what you’re doing is changing the world? Come on. And there’s people that say that actually! But it cannot be like that. That’s something that [only] time and history can’ve solved that.

Rico Gagliano: By the way, I should say, this movie doesn’t necessarily paint the most flattering possible picture of the political artist. Neruda here is definitely a hero, but he’s also a philanderer, he craves attention, he endangers himself and others to get attention. And you actually play a character who criticizes him for that.

So, let me turn that critique back on you: How does one reconcile doing work with a social conscience when the nature of your job as an actor is kind of to say, “Look at me! Look at me!”

Gael García Bernal: Well, I mean, then that is the end of narrative, in a way, no? By that I mean like, well… it always requires somebody.

I mean, at the end of the day, it is not the credit that’s important, it’s actually the work. If you read any poet — any poet whatsoever, from Whitman to Neruda — you might hear the voice of the poet. But really, what you’re listening to is your own voice when you’re reading. Whenever we see a film of a fantastic director or a fantastic actor, we’re looking at the actor, and we are at the same time looking at ourselves.

That’s why also, like… films, for example, have so many awards. They have, like, awards for everything. But really, at the end of the day, if we think about a film that we love and everything, we never think about how many Oscars it has. You know? Like, I don’t even know if “Clockwork Orange” won an Oscar or not. It’s a film that survives! At the end of the day, Picasso’s “Guernica,” you look at it and you encounter the horror of “Guernica” and the least thing you think about is Picasso. If you look at Machu Picchu, well, it’s a statement of humanity.

Rico Gagliano: I’m gonna ask you one of our two standard questions. You may recall these from the last time you were here.

Gael García Bernal: Maybe. I might contradict myself.

Rico Gagliano: That’s possible. We’ll find out. The question is, tell us something we don’t know. And this can be about anything, this could be about yourself, or it could be a piece of trivia about the world. Maybe something we don’t know about Neruda.

Gael García Bernal: OK. I’m assuming that maybe many don’t know about this: In “Neruda,” in the film, there is a moment of exile when he went to France. And he crossed the Andes in the south.

Rico Gagliano: Yeah — that’s how he left Chile, right, he went over the Andes?

Gael García Bernal: Exactly. And at the same time, a little bit after, not long after, through the same roads, in a way —

Rico Gagliano: The same route through the Andes?

Gael García Bernal: — Yes, exactly, somebody crossed from Argentina to Chile. Like, the other way around. And that was Ernesto Guevara and Alberto Granado.

Rico Gagliano: Che Guevara.

Gael García Bernal: On their first journey in Latin America, yes. Like almost at the same time.

Rico Gagliano: Che, who you played, of course.

Gael García Bernal: Yes.

Rico Gagliano: You can’t escape Che Guevara in your career.

Gael García Bernal: Exactly!

Bonus Audio

Hear Gael’s thoughts on Cuba in the wake of Fidel Castro’s death in the audio below.